The following is a slightly emended version of a talk which I’ll be giving tomorrow, Saturday February 1st, at a special panel event, with my friends Thomas Lambert and Justin Smith-Ruiu. If you’re in London and are interested, you can get tickets here.

I’m otherwise working on pieces for various outlets at the moment, and have been pretty busy, but I do hope to be able to return to some more regular posting soon. As always, thanks so much to everyone who has been subscribing, sharing, and supporting.

When I was first asked to be part of this event, I was under the impression that I would be speaking very briefly. So as any good writer does, I tossed out only the finest little nugget of a possible topic—“Gnosticism as the Original Conspiracy Theory” or “Paranoia as a Kind of Gnosticism”—some nice academic-sounding operation like that. I was then informed that I was in fact going to be speaking for anywhere between 15-20 minutes on my chosen topic. And I realized that I was actually going to have to learn something about Gnosticism and Paranoia, or at least appear to know something about Gnosticism and Paranoia.

So I set out to come up with something to say. And at first I felt at a total loss. But then, I thought, the theme of the evening being Paranoia and Literature—well, I may in fact be some kind of expert in the subject. I’m a writer, after all, and I’ve been at times so paranoid as to seriously consider the existence of voodoo-ish hexes and curses on my bodily health, governmental surveillance of the number of times I’ve Googled “how to know if they hate me or secretly like me,” and various small demons tasked with perpetuating my continuing psychological torment and anxiety. Things that, I think, if we were all to be very honest about our darkest worries, are not too far beyond the pale for any of us. Things we have all thought in our worst, most terrified moments, when we feel that special clutching horror that comes with the brief but destabilizing realization that the world is strange, seems to obey strange rules, and that these rules appear to be very clearly organized around preventing us from being happy, or sane.

Now, this is a picture of the world that is strangely suitable to all kinds of schools and modes of interpretation—on the one hand, of course, it is the rhetoric of conspiracy theory, which says: “We know the truth of things, and the truth is that all things have been very purposefully controlled so as to ensure that we do not know the real truth.”

But, taken from another angle, isn’t it also the rhetoric of much modern psychological theory? Psychoanalysis being only the most uncomfortable and obvious example. I mean the kind of psychological statement which says: “The truth is that the real feelings, the real motivations behind my actions—or the actions of other people—are not actually conscious. Behind this illusion of a self, there is really a complex matrix of unconscious desires struggling to be fulfilled, of drives and wishes that must be sublimated or repressed in order for me to function in society.” And where people of previous eras might have imagined that we really did behave erratically according to the influence of planets, or demons, or hexes—we now have recourse to the whole post-Freudian world of terms like “ego” and “repression” and “unconscious desire.”

The metaphors may have changed, yet still, wouldn’t most of us not hold a mentally ill person “personally responsible” for their depression, or their anxiety, or their schizophrenia? Which perhaps implies that something else—an invisible structure, or complex unconscious operation—is responsible. In the Freudian account of the unconscious it’s especially this way, because, again (though I’m now using the metaphor of repression) I can say the same thing I’d say about conspiracy: below the surface, things have been controlled so as to ensure that we do not know the real truth, only now the truth about ourselves.

Or take the case of literary interpretation. There is an entire history of hermeneutics, from old Biblical exegesis, to Jewish Kabbalah, to modern structuralist and post-structuralist, even Marxist, or gender-critical, or postcolonial accounts of literature—basically the whole of what Paul Ricœur called the “hermeneutics of suspicion”—all of which base their view of literature on the assertion that the text—just like the world, in the paranoic or conspiracy theorist’s view—is to be interpreted, to be understood as sign and symbol only, and that its surface is often in direct opposition to what it’s actually doing, at some deeper level. That is: the text isn’t doing what it says it’s doing, and is not actually what it says it is.

This is the basic statement at the root of all these suspicions, I think, and the peculiar vibration we feel—the twinge or the itch which says, with absolute and categorical doubt: “The thing is not what it says it is.”

If you’ve noticed, also, nearly all of the statements I’ve entertained here contained some claim about an actual hidden “truth.” To interpret this way, towards a buried or secretive truth, is always to have some claim to the truth—either vouchsafing one’s own authority, as an experiencer of this terrible truth, or simply as someone who has seen into the truth, and observed that the real authority or mover behind the scenes is impossibly secret, ambivalent, and invisibly, powerfully coercive.

It is, essentially, a statement about God, or the hidden dark truth of God. It’s something like what I’d call the Scandal of Omniscience. In this, I’m thinking especially of Milton’s God in Paradise Lost, because the ultimate text here really is Paradise Lost. For much of the history of the West—mainly the Christian West, and its borrowings from Judaism, though in plenty of Islamic ideas as well—our account of God is essentially a deeply paranoid one. And it says a lot about what we take to be the idea or meaning of omniscience.

In this I’m somewhat following after the great British psychoanalyst Adam Phillips—who I think is one of your best writers, honestly—in a book of his I’m incredibly fond of called Unforbidden Pleasures. “Omniscience is always prohibitive,” Phillips writes, “and prohibition always smacks of omniscience.” Phillips is talking especially about the ways in which we as people—and I would include writers in that category—suspend so much of ourselves, in the name of fighting prohibitions we may never even be aware we are fighting. I see this in myself, in the unconscious aspect of myself as a person—and therefore as a writer—in the prizing of that terrible knowledge, that sense of being initiated into the mystery behind things, and the pride that comes with it, even when the secret I see behind the world seem to be only more lies and chaos. This is something like what the ancient Gnostics referred to as their gnosis. Their arcane knowledge.

Phillips continues: “To forbid something, that is to say, is an omniscient act; it attempts to establish a known future, a future in which certain acts will not be performed, and from which certain thoughts and feelings will be excluded.”

It’s a strange thing to say, that gnosis—or some supposed knowledge of the grim, overly-constructed reality of the world0—is a way of also ensuring what will not happen, a way of foreclosing on the future. There’s a way in which knowing itself, or the obsession with knowledge, is just another prohibition—the quest for ultimate knowledge, or omniscience, being the biggest prohibition of all. Because what it denies to us is the freedom of not knowing, the freedom of not being able to see the future; that is, it denies most of the things which, I would say, define freedom itself. The same goes for all this psychoanalytic search for deeper meanings in the Self: part of the reason we go searching for meanings and motivations—and in our contemporary literature and cinema we’re absolutely unhealthily obsessed with pat psychological character motivation—is precisely because of what it prohibits in us. It substitutes a knowledge—however awful—for the real freedom that comes with acknowledging we do not, and perhaps cannot, know.

In Paradise Lost, God forbids Adam and Eve a very specific thing, but in his omniscience, he knows that his newly created human beings will of course do that very thing. To me, this implies that Milton’s God ultimately wanted this to happen, and made everything a certain way, and created the world and human beings exactly as he did, for this reason. If he had wanted otherwise, he simply would’ve made things differently, and the Fall of Adam and Eve never would have occurred. For Milton, of course, this made God a kind of cosmic author, or screenwriter who had written, cast, and directed the whole film of human destiny, ensuring that our Fall was part of a final redemption by Christ.

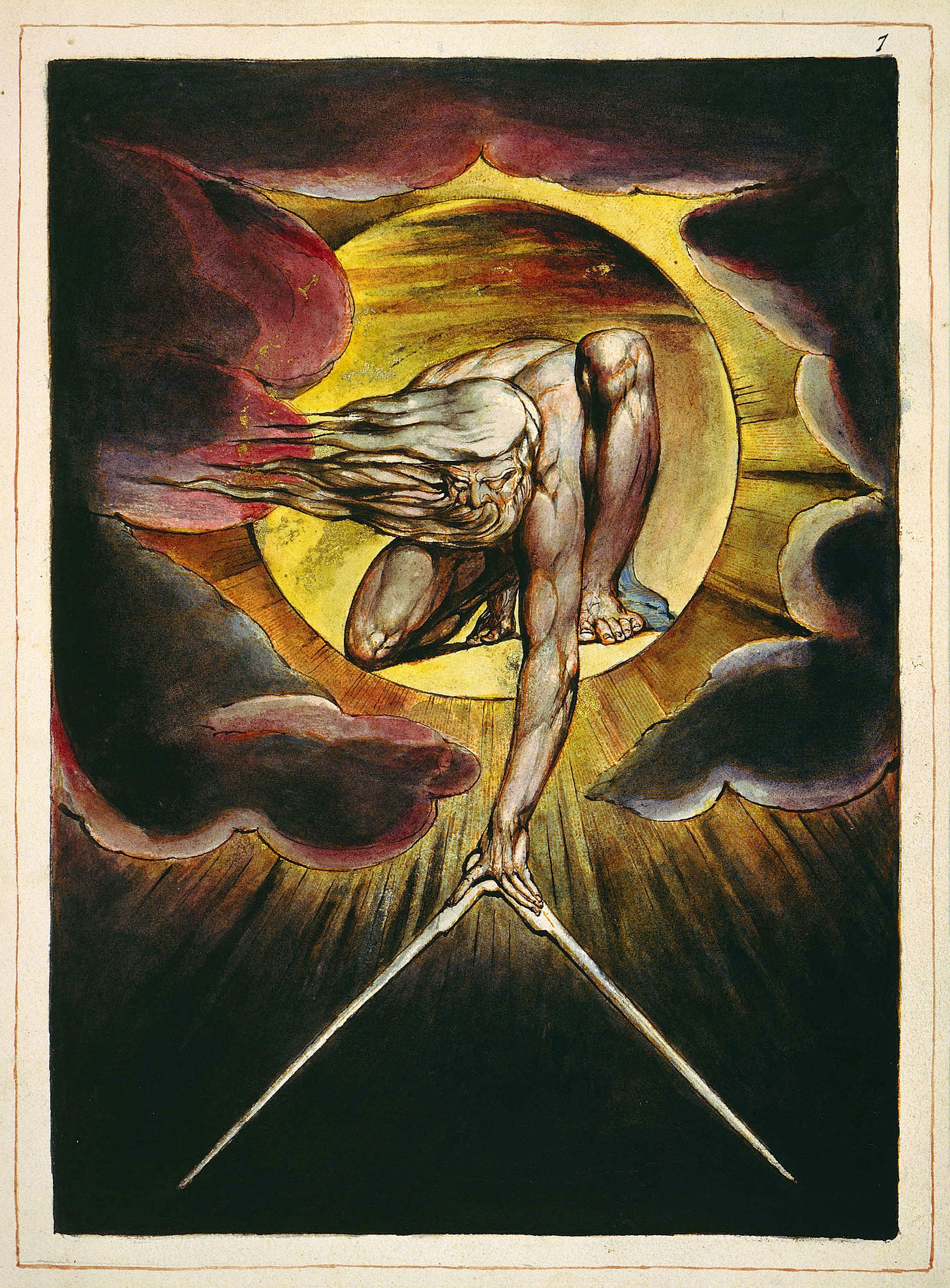

This is all well and good, except that it has never left anybody but Milton satisfied. It’s these paradoxes which led the poet William Blake to assert that Milton was in fact “of the devil’s party, without really knowing it,” precisely because he had made an argument for the absolute horror of God’s omniscience and the necessity of rebellion against it.

This then places us—the paranoid, the conspiratorial kinds, the literary interpreters, and psychoanalysts of the world—in the position of little Lucifers, who go out into the world and preach to all these fresh-born Adams and Eves the gospel of “truth”, that behind the scenes, a horrible, jealous God is in effect constructing and puppeteering everything. The things he has forbidden to us are inseparable from his omniscience, or his belief in his own omniscience. And we are left to either find comfort or horror in our final powerlessness.

Now, into this role of Lucifer, the Promethean artist, or person—who is always coming up to his audience, and claiming to pull back the curtain, revealing the way things “really are” or claiming to possess knowledge of the conspiracy against us—this role leads, I think, inevitably to Gnosticism.

Now, I call this Gnosticism, not just because I want to associate it with the historical body of religious thought which makes up Gnosticism. Even more than that, I want to call it Gnosticism as a trope—or a figure—for this way of looking at the world. Just like the historical Gnosticism and all its heresies formed a kind of repressed underbelly of the institutional Christian church, I see our paranoid Gnosticism (which is a cornerstone trope or mode for contemporary life and literature) as the dark underbelly of our more and more interiorized, psychologized sense of world and Self.

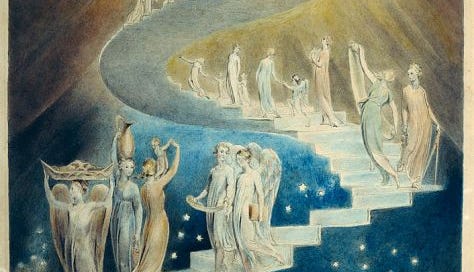

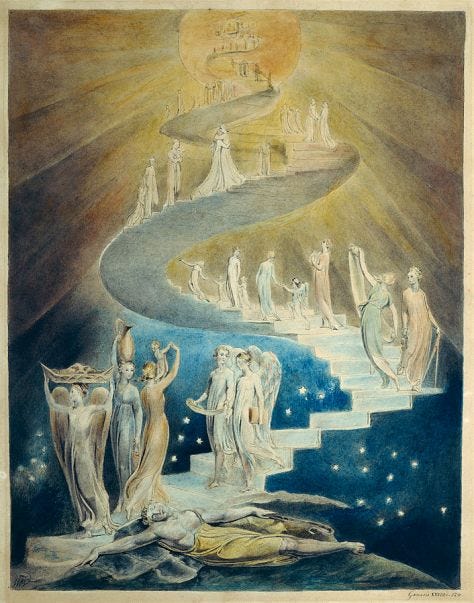

Many Gnostics believed that the Fall was the same as the creation of the world: that it was created by a demiurge (in some readings, the Yahweh of the Old Testament, or what Blake called Urizen, the Ancient of Days) which falsely believed itself to be the highest divinity. And we were all fragments of the true divine pleroma—the fullness before creation—which had fallen into matter. So, in this life, we have to come to grips with our inherent hidden divinity, be initiated back into the mystery, and transcend through the many spheres and levels of existence to reach back to that true divine unity.

I’m interested in this, largely because I think most conspiratorial or paranoid thinking ends up finally coming back to this fundamentally Gnostic point of view. Like many Eastern religions, it confirms that the world is ultimately only an illusion. Where it differs from Buddhism and Hinduism, however, is in the way it declares that this illusion is purposeful. It is being done to us. The powers of the universe are deliberately hoodwinking us into forgetting who we really are. Think of The Matrix, for instance, which is an incredibly gnostic fantasy. Really—to complement my man Justin’s take-downs of the proponents of so-called “Simulation Theory”—this is what everyone’s argument for the world-as-simulation boils down to. Someone who has it in for us has fixed it all against us.

Now most of what I’ve said for me represents the kind of picture of the world I’ve had to let go of, and move on from, in order to actually be a person, and therefore an artist, in the world. I’m not a Christian, although some days I desperately want to be. As the son of a preacher, I find it’s nearly impossible much of the time. But I used to be quite obsessed with Gnosticism, to the extent that I was profoundly depressed from Gnosticism. I see all my own lowest moments of horror, mental illness, paranoia, despair—I see it all there.

So I want to say two things to that. First, the actual ancient Gnostics were far more complicated than this picture. Spend a little time with the contents of the Nag Hammadi library, for instance, with texts like the Gospel of Truth, or The Gospel of Thomas, and you’ll see there was an incredible variety to the kinds of things being thought by those people. One important thing to remember, if we’re going to take Gnosticism as a mode or trope, is that it was one among many interpretations of old stories, and that it itself was hardly a unified body of thought. When we read of Irenaeus of Lyon in 160 AD, denouncing the Secret Book of John, or Athanasius of Alexandria in 367 AD, decrying these heretical texts and insisting on the canon of 27 books we today call the New Testament—we have to remember that the creation of a unified and institutional Christian church itself played a large part in creating the mystical, dark idea of gnosis.

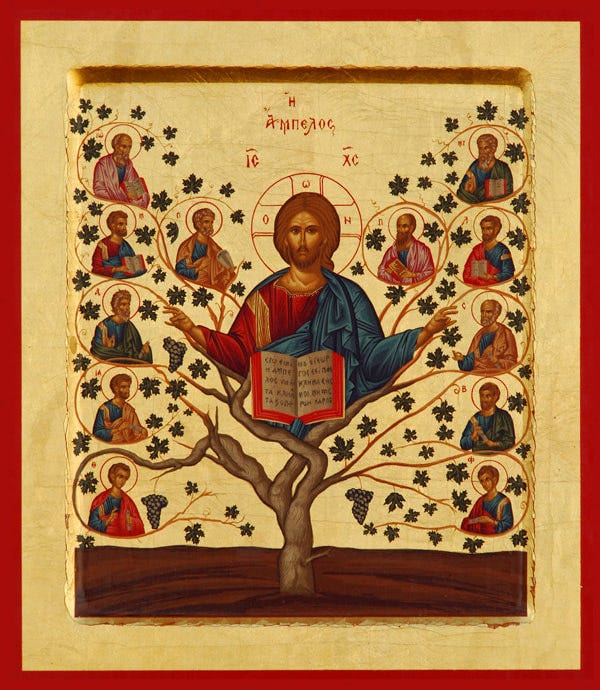

Next, I want to oppose the Christ story itself to Gnosticism. Because the only way to combat or undo a particularly seductive story is to tell a better one. And for all our paranoia, for all our Gnosticism, we are also inheritors of a story that is in many ways even more radical than any conspiratorial vision of the world. There in the foment of the Levant under the Roman Empire, with Greek philosophy and Neo-Platonic ideas of divine unity, shading into Manichaeism, bleeding into the old mystery cults, and the new Gnostic ones, Hermeticism and its priests, alchemists, any one of whom claimed to be the bearer of the secret knowledge at the bottom of the world—into this foment there came a much stranger story.

And it said that the actual being responsible for the birth of our universe did not in fact conspire against us, but came and lived as one of us, lived the whole life of a human, and died in pain and torment at the hands of the world’s most powerful empire. I still don’t know what to make of it spiritually, but speaking as a writer and as a modern person, I see it as an argument for something more difficult, and in fact less prohibitive than the gnostic vision. It is, really, an ultimate argument for freedom, an admonishment to paranoia, an opposition of essential grace to conspiracy. As a metaphor, as a symbolic story, which we keep telling to each other, what Christ “means” in some literary way—and here I should say I don’t see literature as being in any real way different from life—what Christ “means” is that there is actually no initiation into the mystery required, there is no “seeing behind the curtain,” there is no “hidden thing.” What in the ancient world had belonged only to oracles, cults, priests—this knowledge was now open, free to every person ever born, all through time, saying that we are all equal before the divine, and the divine has forgiven us for any wrong we could ever possibly do, to it, or to each other.

So I think, we can be like Gnostics and worry about the secret teachings, or we can tell a different story, which is maybe the craziest story any human being has ever told. Because it says very plainly, the ancient gnosis is no more, there is no hidden knowledge—the greatest lie is the statement that the world is a lie. There is no conspiracy, nothing is preordained, we are free to do what we will. We don’t need to reach deep into ourselves and know the deep truth, we don’t need to reach up and know the ultimate truth of the universe. We are free to simply live. Secret motivations, reasons, hidden mysteries—they are nothing compared to the freedom that comes from accepting the central mystery. Which is that we do not know, and do not need to. What one great anonymous writer of the Middle Ages called “The Cloud of Unknowing.”

We live in a paranoid time. I don’t know what we can really do about that as writers. But I do know we have to come up with our own tropes, metaphors, and language for this. For this grace, or that universal thing, that freedom for ourselves, the freedom from the obsessive cults of obscure knowledge. The world has to be wide open for play—we can’t let our suspicions keep us from it. That’s all I really have to say.

Great writing! I love the literary bent on this, so sorry for answering in plainer terms.

I don't think we can say the gnostics are *wrong* about there being a veil... it's a huge veil, and an evolutionary one. Evolution is a blunt designer, blindly optimizing for present reproduction; truth, happiness and long-term concerns can only fall through by near-accident. Our symbolic thinking faculties are so crudely tuned that we're liable to get terrorized by our own random thoughts. We reify our own thought patterns as if they were objective, and then wonder why the world doesn't work like it should. We fall for zero-sum social games all the times. But then the gnostics themselves fall for the veil of paranoia, and reify a mischievous conspirator in chief. That's where they get it wrong, as you yourself say. It's the silly world of Matrix, with its cartoonish villains running the show.

So "seeing behind the curtain" is absolutely needed, because there is a lot to see, and a lot of pressure not to see. Contra your the later part of the article, reaching deep into ourselves, looking for the deeper truths, is very much needed! Indeed your whole article, and so much human intellectual endeavour, and so much of literature, is precisely trying to do that. It's just that the *paranoid* mode of doing that is no longer called for.

Then the mainstream Christian story you contrapose.... isn't that also a conspiracy? A God who conspires to become human in order to redeem humanity is still very much shaped as a conspiracy. It's the story of a God who has a narrative in view, the story of a "good" top-down manipulator who will mess with us humans to bend things towards His purposes. Taken at face value, it devolves into the soothing myth of the adult in charge.

So yes, whatever we want to call it, I agree that we need to come out of paranoid thinking, and finally figure out that *there is no conspiracy*. Neither the villains of Matrix, nor the parochial Good God who bends to our human-shaped sense of the favorable or the good. In naturalist terms, it's an evolutionary, bottom-up story. But if you have a sense of God or spirit, then it means giving God back its transcendent freedom. As you say, wide open for play.

As you say, we do have great difficulty inhabiting our bodies in this life, in this world as it really is.