How Ulysses Taught Me to Read Again

The Child is Father to the Man

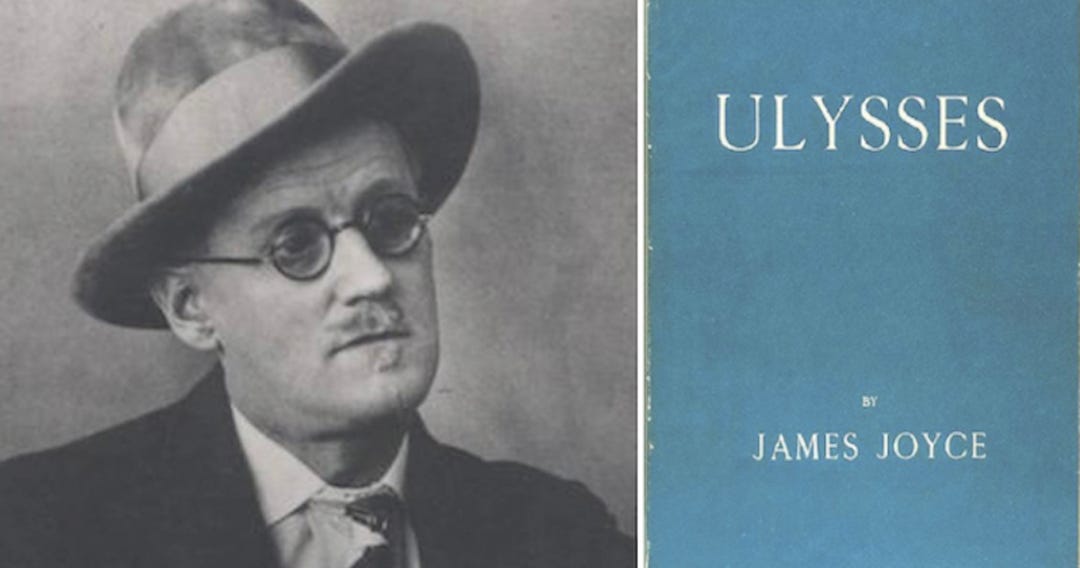

Note: this post was originally meant to run on the 16th of June, Bloomsday. I decided to push it back in order to put out a few other posts, though mostly because my mind was occupied by a bit of a micro mental health crisis. Then I put it off another week, and had another crisis. Then I had another, and another. I considered having a fifth, but I’m beginning to suspect it’s just not worth it. So now I’m here a full month late to speak to you about the man who became my literary father.

Midway along the journey of the book I woke from a dream and announced (I don’t remember doing it: a journal entry from the time tells me I did) that the book had taught me how to read for the second time in my life. Not long afterwards, I realized this was true.

It’s hot in London. I’ve been profoundly depressed, putting off work I know I ought to be doing on my dissertation, dreading the search for new digs, still limping under the knowledge that I really have no clue how to run this Substack, no sense of mission, only sheer spite for the content mill, spite for my own greediness for clicks, positively no idea how to yoke my worst anxious phases to the kind of schedule apparently necessary here. I’d wanted to revisit the novel—the great Joycean totem—which gave birth to so many new worlds in my own mind; which fathered in me what I can only describe as an ancient reality and obscure purpose: new-born, hale, angry, and at all hours, fitfully squeaking its way out from beneath the rock of my static, depressive, bed-bound brain.

Instead, I pissed away weeks lamenting the unchangeable facts of the world—every day I pissed away my precious time. Yet what was I going to write, anyways? Each time I stare at this “page,” each time I confront the dull lit blankness of the screen, trying to summon something worth somebody’s time; whenever I see dozens of smarter, better, more optimized, more eloquent, more studied pieces by the expert writers on this platform—I feel I’ve fallen farther and farther behind. I’ve abandoned my poor artfather James, abandoned the mission his book made clear to me, abandoned the bright bluegreen beauty of its ancient oceanary scenes. Instead I only drown in more particularities, more curation, in digital noise, and daily apocalypses. I get no closer to the real, the beautiful, or the true. Like a philistine, I start to suspect that these are mystifications. The world falls away; distraction rules in my stupid head again. It’s awful, and it feels like nothing.

Tonight and every day and all through these weeks and really every night I’ve been listening to Rachmaninoff’s Vigil, one of those center-of-the world masterpieces which manages to hush even the bitterest atheistic voice in my mind. I wish I could see the fields in Russia, in the Ukraine—see those remnants of icons by Rublev which I’ve heard so much about. I’d love to take the train from Paris, going slowly East, watching the West fade behind me, and shedding all my meaningless details, hewing down closer to the raw, to the grand and the austere, figures of the East. Puffing steadily towards the bare warm Orthodox heart, which I imagine still lies deep, in the passage of the Volga, in the wheat-fields, in the steppe. Ancient truths there, I think: things still hidden away from any fretting, spectacled Western eyes.

That’s what Rachmaninoff’s piece makes me think of most—those glorious tropes, the unforgiving Slavic silences, of the mythic East. Makes me think of Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev, a film-beyond-all-film if there ever was one; an experience I return to every few years just to gather up the remnants of my poor fatigued attention and attune them again to the right, proper, cosmic sense of the world. The lost medieval condition I long for: re-attuning to immensity; to the gorgeousness of death. Something I experienced for first time this year: the beauty of death. The power it holds, in a room; the way it re-organizes all priority; how it re-organizes time. And at its most insistent, how it creates reality again, drawing boundaries around what was only a blur before. Then you have a picture of the thing. Finite, beautiful.

It’s exquisite, that picture. But it stretches—it stretches thinly across the world, and cannot stretch forever.

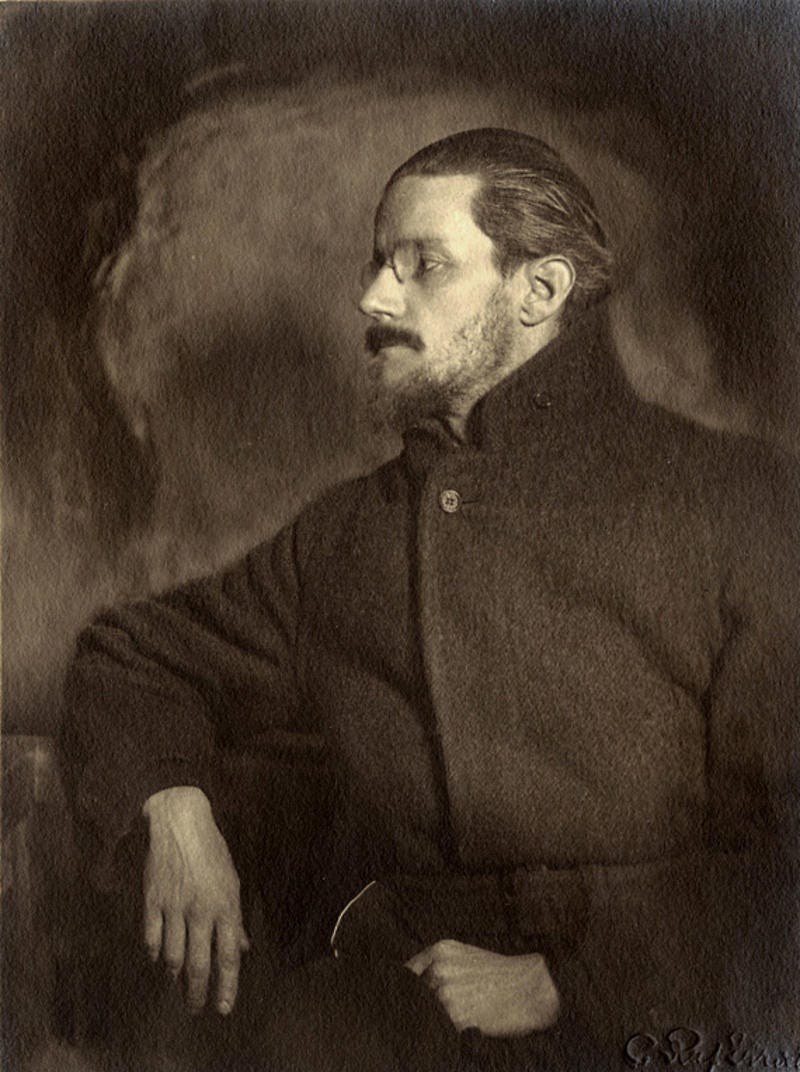

This is my father; like him I thought to be a singer, and ended up a writer instead. So far, so cosmologically far, from Russia, and all those primal totems of an Orthodox beauty, lies the little Island of him, my artfather, the Dubliner of Trieste. Makyr of the Agenbite of inwit, the deadly candlelight of conscience, and all it darkly intimates. “These heavy sands are language tide and wind have silted here.” When I think of Ulysses, I think first of the Tower. The book opens (as all life opens) in the bosom of the ocean; begins (as all mind begins) descending from that lofty tower garret, for a breakfast with an Englishman. The tower must be Yeats’ tower; perhaps it’s Byron’s Childe Harold’s tower, too. It is also, as Buck Mulligan confirms, the Omphalos, the navel of the world, home of the Oracle, seat of all mental powers, spot where divinity enters into the mundane. From there we sprawl: a day in Dublin becomes the origin and horror and tragedy of the West, all its odysseys and tales, becomes the beautiful worldly-weary thoughts of the quaint Falstaffian Bloom, and the tragedy of the lost son Stephen Dedalus; becomes a metonym for all minds, times, oceans, peoples, places. Life is elided in the tide, which beat on these heavy sands forever.

The first time I read Ulysses, I couldn’t make it past the beginning, the “Telemachus” section. Not for want of understanding, but for a glut of it. I couldn’t keep going, couldn’t move on, because I had to return and re-read the entire piece, the book’s first fifty-or-so pages, again, and again, and again. Probably three or four times I read it whole, and even then I still didn’t want to go forward. How could anything measure up to that? The monologue of Stephen Dedalus is a roiling, tortured scherzo on the whole corpus of Western literature—an exorcism, perhaps, of Joyce’s own exhaustive attempts to build a worldsoulscaffolding within his own psyche. “I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience and to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race.” So Stephen declared at the end of The Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. In Ulysses, we find him reeling from the death of his mother, taking eternal guff from stately plump Buck Mulligan, and rhapsodizing inwardly about all the hell this uncreated conscience of his race has been wreaking on his heart, soul, and mind. All the agony of the agenbite of inwit.

Whereas Leopold Bloom passes through his day with a kind of gracebefuddled capaciouswit, capable of containing and generally navigating the actual world, young Stephen is all angles and whirlpools, jutting out sharp against everyone and everything, while deep down adrift in a mind filled with dark theologies he wishes he didn’t believe, tangled histories winding around each other—those nightmares he wishes to wake up from. This is the difference between father and son; between wisdom and brilliance. Bloom, like Falstaff, is Joyce’s rushing out towards the borders of the world, to find a mind large and fleet enough to negotiate its own morality (and mortality). Bloom is no Last Man, but he is a Good Man. And not for being particularly good at anything, but for loving life itself. Stephen, Joyce’s autobiographical Hal, is the kind of morbid genius whose wit might betray him, without a decent teacher—he’d be just as likely to become a Machiavel, as a Montaigne. Joyce is fathering himself, here, of course: just as Odysseus finds his boy Telemachus, so Bloom and Stephen find themselves as they collide in the night, and Bloom tries to give the boy a bit more access to life, or to his own soul’s beauty.

How exactly does one read Ulysses? Cover to cover, most likely. Perhaps with one of those detailed guides, though if you’re like me, you may find yourself simultaneously reaching for those speculative details, yet sometimes still only wishing to let yourself bathe in the prose as it washes by. A friend of mine told me that for the “Circe” section (essentially an over-one-hundred-page absurdist play), he had to go hunting for explanations. Yet during the “Oxen of the Sun” (which traces in fine-point mimicry some one-thousand years of English prose styles, from Aelfric to Thomas Carlyle, while supposedly corresponding to the nine months of human natal gestation) he simply sailed. For me it was the opposite: I needed to leave small notes based on others’ best educated guesses about the exact subjects of the “Oxen” mimicries, but for me “Circe” was a nearly-brainless romp.

Could I have figured out on my own that “Sirens” is designed to be a bit like an orchestral performance, including a warm up in which “instruments” play their practiced little mixed up riffs (or images)—the two barmaids, the car honks outside, Leopold Bloom in the corner, Stephen’s father serenading the whole of the public house—of what will be played more linearly afterwards? I’m not sure. Even if I didn’t, would it have been any less incantatory? Any less remarkable?

Much of Ulysses is like this: there’s the conceit (even that global conceit, of its being approximately mapped out according to chapters of the Odyssey), and yet it is not exactly necessary to get the underpinning experiment in order to appreciate its extraordinary effects. It’s a bit like wandering into an opera and discovering no one’s provided any programs. It doesn’t change the beauty of the music. You may read Molly Bloom’s final, ostensibly infinite punctuation-less soliloquy, in one single breathless go—or you may break it up, and pace yourself for breathing. If there is anything which Ulysses teaches it is this: read as you will, as you must, as you feel you have to. We are dealing with ancient things—old stories, old wounds. Tales of a psyche that is not individual but numerous: a language which reaches back to the very start of ourselves, in whatever prehistoric mist we came from. From the call of the Aulos and the invocation of Calliope, at the start of the West’s weird story—there has been only one tale, which grew steadily with the telling. The complex maps and labyrinths of Ulysses are merely the efflorescent inevitable of that original literary need. Ulysses teaches that filigree is a gorgeous envy: envy of the centrality of the original story. The Baroque; the Byzantine; the ornamental are glorious insofar as the church they decorate remains. And the church of Ulysses may be entered into at any time of the day; the day is forever. It repeats and repeats, and never ends. The doors stand open, and any traveler may come, may wander around, discovering the history that’s been hewn from the rock, and then exit—perhaps taking a bit of the spirit with him.

Of course all of this—religion, myth, the West, fathers, sons—is another way of saying that what Ulysses is ultimately about is not even Homer’s story. It is about how we go about perennially fathering ourselves (if we can forget gender for a moment, and see “father” here as the archetype of a seeding principle), giving birth to ourselves, emerging violently from the skull of ourselves, self-procreating from the hot sea foam.

It is all another way of saying that what Ulysses is really about is Shakespeare. The Bard, I think, is the key. And this is where Joyce began to teach me to read again. Not merely through the magniloquence, the gleeful enormity, the ridiculous learned musophony, of his prose. But deep—deeper, even. For me the central section of the entire book-world-cosmos-soul-psyche is “Scylla and Charibdis,” the scene in which Stephen holes up with various tottering poetasters in the National Library, and unveils his obscure disquisition on the ghostly historical phenomenon which was Shakespeare. Proving, as Mulligan says, “by algebra,” that in Hamlet Shakespeare becomes his own grandfather. The rest of the Shakespeare corpus is read for the most ridiculous, rhapsodic, ultimately-almost-convincing biographical development (making New Historicists everywhere turn in their bed-graves: Anne Hathaway as the raping Venus of Venus and Adonis; evil uncles as Edmund, Richard, et al.; young dead Hamnet for Hamlet; Perdita, Marina, Miranda for his daughters; the love affair with the Dark Lady, and W.H.; constant tales of exile from home; then the finale to the career in the Romances and collaborations, and the restitution of all things, at home with Anne again).

What Stephen has to say is pure, but darkling:

Sabellius, the African, subtlest heresiarch of all the beasts of the field, held that the Father was Himself His Own Son. The bulldog of Aquin, with whom no word shall be impossible, refutes him. Well: if the father who has not a son be not a father can the son who has not a father be a son? When Rutlandbaconsouthamptonshakespeare or another poet of the same name in the comedy of errors wrote Hamlet he was not the father of his own son merely but, being no more a son, he was and felt himself the father of all his race, the father of his own grandfather, the father of his unborn grandson who, by the same token, never was born, for nature, as Mr Magee understands her, abhors perfection.

At the death of his own son and his own father, Shakespeare—the ghost of all the canon, everywhere and nowhere, godly—returns as the old ghost (theatrical legend says that Shakespeare played the part) of his own son’s father, banishing his own father forever, and thus creating himself. Yet Stephen’s extraordinary claim for Shakespeare must be seen for what it is: a fundamental, theological statement about the creation of all things. We are, at the end of the day (which is night), forever indebted to the fathering of us: forever indebted to the creator or creating spirit which gave us breath, and made us move, and formed our brains from the dull wet clay. We owe everything to it. And yet to go on, to go on making, to go on searching for the completion of ourselves, to go on hunting for the beauty in one another, or in our art, or in our makings—to do so, we must monstrously, ghostfully, gloriously, beautifully, and death-defyingly create ourselves. We must father ourselves again.

All Ulysses is, at heart, is a meditation on the theme, which is the only theme. The cosmic theme. Pro-creation and auto-creation; responsibility and delusion. The necessity of Ruach and Pneuma, and yet the necessity of the furor poeticus also. This is where Shakespeare is allimportant, because Shakespeare is how we have created ourselves. He is our ultimate ghost—like God, we cannot, and should not, know him. History has seen to it that we should know nothing of his own person, or his mind—only his creations. Which is how we should properly know our creator, our father. In making him, we have made ourselves, and Ulysses stands at the very moment (in time, in space) where humankind discovered itself in a world, in a scientific-technologic dream, and in a crystalline moment of agonized waking…it stands at the moment where we saw just what was made and, through making it, how we made ourselves. More than a century later, we still can’t contain the insight. Somewhere Meister Eckhart says it is only through the son that we may know the father—or he, us. Without Homer, without Shakespeare, without Ulysses—without our many fathers—how would we know ourselves? The capacity to fool ourselves, to convince ourselves that we might father ourselves—that we might make new things in or on or through ourselves—is the ultimate divine capacity. And it is the only thing which might speed up our own creation.

As Stephen says:

Every life is many days, day after day. We walk through ourselves, meeting robbers, ghosts, giants, old men, young men, wives, widows, brothers-in-love. But always meeting ourselves. The playwright who wrote the folio of this world and wrote it badly (He gave us light first and the sun two days later), the lord of things as they are whom the most Roman of catholics call dio boia, hangman god, is doubtless all in all in all of us, ostler and butcher, and would be bawd and cuckold too but that in the economy of heaven, foretold by Hamlet, there are no more marriages, glorified man, an androgynous angel, being a wife unto himself.

And yet we’re not in heaven—not yet. We’re not androgynous angels, or wives unto ourselves. We’re complicating fathers and procreating mothers, sons and daughters, confused and confusing. As small as a day and as big as a world.

It’s hot in London, again. Now I’m listening to The Goldberg Variations arranged for string trio. I love how its structure spans more clearly through those three bright voices, in the more specific registers: counterpoint on strings is more obviously conversation. The atheist is quiet again in my head. Where can he go? Bach opens the world too wide, and yields up all its intimate connections in the circumference. Anyone who would try to ignore its patterns would misunderstand every note and die deafly. Anyone who would see them would recognize they’re endless.

A woman recently entered my life, and left, and that time was over. Most of it was painful, yet some of it was lovely. The rareness of a mutual affection but still, to love is to choose. We cannot afford not to choose. I only know I never wish to be dead again. My body hurts most days; dysfunction and disease seem infinite. But I’ve flipped open the novel again, and I’ve heard my father’s voice, quiet, constant, just beyond the veil, in that cloud of unknowing. There’s a deep and obscure mission in it, coming from it. It glows from the center; it illuminates from within. I read. I meditate. I pray. And I think (as I always hope to think) that there is no way now to quit.

This is a beautiful essay Sam, thank you for sharing it. I’m definitely still early on in the Ulysses journey myself, but I feel that it will be worth it if/when the book “opens up” to me.

Without trivialising the genuine tension you might feel from not “optimising” this platform, I would agree that not being quite attuned to its demands is far from something to be ashamed of. What you’ve brought to the table already outweighs the daily click-farming and wave riding that goes on here.

“Let’s go together, you and I. You’ll cast bells and I’ll paint icons!”