Any animal can say to its friend: “Look out—there’s a predator in the bushes!” Animals have their squawks and howls and clicks. Even the grass speaks in its way. What we call mere communication is likely universal; DNA itself may only be another way of speaking, carrying information forward through time. So certainly, any animal could probably say to its companion: “Look out!”

But after the danger has passed? Only a human animal could say: “Remember, last spring, when we were nearly eaten by that lion…?”

By itself, this is sophisticated enough to mark a very different degree of consciousness. But that this might spill further into a story— “Yes! I remember. We’d been walking all day and had just found some deer tracks. Night was falling. Then we saw the lion, creeping through the trees, almost a quarter-mile off…” —that is a new thing entirely.

At a certain point, once told enough, the story may even reach such an advanced state that it becomes a kind of emblem for all stories: “So we made camp. And all the night we never slept, just looked out into the lion’s eyes, blinking in the darkness. Until dawn, those terrible eyes never stopped staring, glinting in the light from the fire. Yet in the morning, we discovered the lion had gone. We found a path of blood where it had killed one of the deer in the night, and dragged it off to eat it. So that it couldn’t possibly have spent the entire night staring at us from the trees…”

Then the mystery—that unexplainable moment at the heart of the story—may be felt, by all who hear it, to be the same as the mystery of existence itself. This is the moment in which we could finally be said to be human, in the way all people feel themselves, distinctly, as people. United with others in shared memory and in shared orientation—towards that mystery.

In some sense, poetry may begin here, too. Perhaps people start to create rituals for themselves—every week, they leave meat out for the lion—rituals requiring binding words, which take on the character of incantation: not to say them becomes dangerous. And as in Kafka’s parable of the leopards breaking into the temple, all new danger and new information will become integrated into the ritual as well.

This is primal, Pagan magic. Soon its more dangerous form, black-magic, enters into the world. Now different words are invoked. Not in the manner of the popular or sacrificial ritual, but in order to get it over on the world. Praying to the mystery for power over the mystery. Not just the skills to live with it. All human psychology, philosophy, and science might be called outgrowths of this ancient dialectic. That is: which to choose? To choose ritual, and the language which integrates? Or to seek self-aggrandizing mastery? In the Occult landscape, we find many conflicting examples of each: philosophers seeking ways to live with the world through mastery of the self; alchemists trying to change literal matter, but in the name of knowing God. Most often, they don’t understand the forces they let loose. Most often, they are Faust.

But poetry, though it takes part in all of this, is something else, too. More even than in ritual, poetry takes life through the story itself: its tellers begin to understand that any single aspect of a story may be simultaneously understood to be any other thing, as well as potentially being all things. Then comes irony, necessary for all stories. And not merely the kind of irony evident in saying one thing while meaning another, but a cosmic and expansive kind which may say something and yet mean nothing, which may also say one thing and mean everything. The discovery that language has endless analogical properties: the lion is the mystery, yet so is the fire, and so is the darkness. We’re mysterious ourselves—why do we need fire? What goes on in the darkness beyond what we see? What are the limits to our knowledge? And what is the lion prowling at its edge?

To the ancient agrarian age in which human sounds were initially written (out of necessity, at first: What season are we in? How many sheep did we trade last spring? How many will we need to trade this time?), poetry was understood to be the mode of delivering the story. Though to say so might already risk differentiating such “poetry” from “prose,” a distinction we should be wary of foisting on older ages.

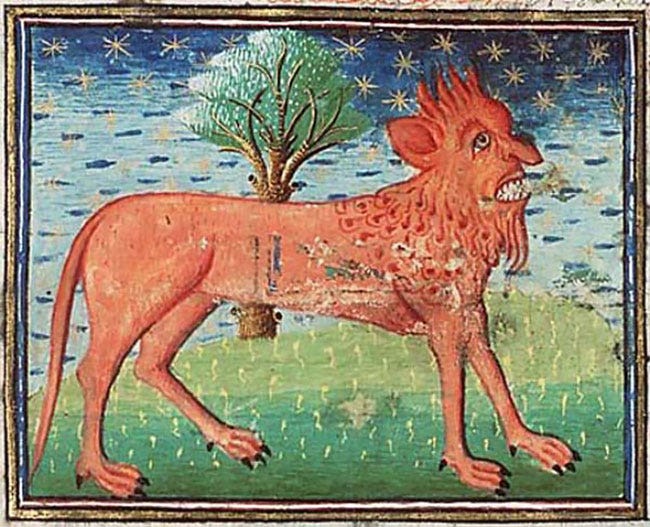

Soon we find people in cities, and the gods they bring with them, and the histories of the exploits of each. The lion survives in the stories told to children—though also in the stories of heroes and gods. It’s understood the lion itself may be a god. Not the way it was in tribal days, when it was a god-animal, but that the god might turn itself into a lion, in order to make something interesting happen.

The poetry of this era is the saga, the myth, the epic cycle—poetry as a unifying principle for all narrative, aspiring to the most apt or artful locution and rhythm required for its recitation. People have begun to understand that some poetry is in fact more beautiful than some other. Or at least, in some emerging classical sense, more correct. Certain modes of address are more appropriate for certain occasions. One poet may compose more beguiling stories; one singer may manipulate meter in a more virtuosic way. Poets enter into competition with one another for the ear of the people, most especially the rulers and the powerful (the birth of the ode and panegyric), who could have enough resources to endow a poet for a lifetime (the birth of patronage)—the poet becomes a professional, not merely the inciter of ritual, or a shaman, or a magus. Though each of these roles will always remain possible for the poet to play.

There’s only a short step from this to drama, where the ritual is knowingly acted. Then on to pastoral, where the lion is happily banished and peace is declared in the countryside. And it’s a short step from the tales of the loves of the gods (and the loves of the heroes) to the loves of the poets themselves—so the lyric is born.

And the poet could be all of these: the seer, the keeper, the oracle, the professional, the singer, the entertainer, the magician, the lover, the hymn-writer, the layman, the totem-maker, the praiser, the vilifier, the actor, the playwright, the visionary, the craftsman. Best is the poet who figures out how to play with them all.

. . .

We may still yearn to be able to speak in an elevated poetic language—with a high poetic diction, antiquated term—and yet we’ve mostly abolished it. Blame the fetish for everyday speech, which rises in a cycle with the taste for the more “artificial.” Or the distaste for what was once called an Aureate Diction. Aureate: meaning high-flown, formal, oratorical, aloof.

The average reader today probably associates declamatory, heightened poetic diction with their only remaining public examples of older language: Shakespeare and the Bible. Much like Spenser’s The Faerie Queene, the King James Bible was written to sound deliberately archaic. But Shakespeare was really of the other cycle. Part of an era moving away from flowery, continental conceits—towards something more resolutely English. Something earthier, more medieval. Some scholars even see a shift from the Latinate Renaissance towards the Gothic Middle Ages unfolding slowly across his works.

After the Restoration, the neoclassical eighteenth century often struggled to parse Shakespeare’s “rugged” meter, just as they felt deep ambivalence towards his characters’ violence and licentiousness. For that age, his words and sounds were too everyday, too “barbarous,” his rhythms too variable. They didn’t makes sense to thinkers turning back to the continent and attempting to revive an ornate, graceful (and above all correct) Augustan plan.

That age died as well, partially at the hands of Wordsworth (and German philosophy, and the French Revolution)—in the preface to the second edition of the Lyrical Ballads, he justified his choices as “a selection of language really used by men,” rejecting such high, formal poetic diction. All Romanticism is full of the notion. Now every time someone comes along and says poetry should get off its high horse, should be no different than the sounds of the street—no “thees” and “thous” or “sunsets red” or “craggy peaks of burnished brine” or “drink to me only with thine eyes”—they’re being more than a bit Wordsworthian, whether they know it or not.

But how often we have these things backward! Read most poetry before the Modernists, and you’ll encounter a syntax more flexible than anything we could write today. “Thou who maketh the season red with bloom/Thou who whispereth with the prophets old…” To us it’s impossibly heightened, aloof, ridiculous—“You, who make the blooming, red season/You, who whisper with the old prophets…” —we might rewrite it, and it might not be so bad, but hasn’t it lost something beautiful?

There’s a world of difference between “old prophets” and “prophets old”—but while we can only abide writing the first, Shakespeare was free to write either. And “maketh” and “whispereth”? Only grammar forms, meaning nothing fancy whatsoever. They seem like that to us because we believe the language of that time was more formal, our own more informal. We’ve spent centuries with Bible English ringing its immense cadences in our ears. But today English words are more rigidly ordered than ever. Compare any current piece of prose to the freewheeling syntax of even minor, early Shakespeare:

Methinks I heard a voice, Arsenio:

The herald voice of that godless kinsman,

Cleped Maugranio, whom would strut betimes

Across these very walls, and at cock’s crow

Be heard to give good grief to the dawn,

When that self-same night, in such lunar pique,

‘A would grunt and grin, men say, a very

Bedlamite. Nor halt nor rest one brief span,

But howl and bay at the crosswinds ‘til morn.

And men say his voice lingereth still,

Like Proteus, a-changing i’ th’ air

Which bloweth in with Zephyrus at even,

And cometh to rout the souls of his kin,

Stalking anew the ivied walls and towers

Of his ancestors. Aye, Arsenio,

I have heard the age-chidden voice of the king

Of my father’s fathers, his ghostly mien

Did breathe our air again but yesternight,

Incensing it with foul and spectral aires,

And odours hot as from hellmouth. I heard

And felt it, and I have been ill afraid.

It’s our language which has calcified—it’s we who are more uptight. Current Anglo-American English is about as regular in its word order as Mandarin Chinese. And when a contemporary person goes to mock something they find snobby, dropping “Thou’s” and “Thee’s” into their sentences, they hardly know it, but they’re using something which was once informal, but was slowly scrubbed out in favor of universal formality.

When an English speaker goes to learn a Romance language, what do they find? Both an informal and a formal address. And it’s difficult to translate—because we have no such difference. Though we used to: “Thou” was the personal—the intimate. One used it with loved ones, and one used it to speak to God. “You” and “Ye” were formal addresses, to use them with an intimate might have been considered rude. Hamlet, as he grows to care for Horatio over the course of his play, changes from “you” to “thou.” It signals his affection.

But now “you” is all we have. Millions of English speakers, when they go to mock their own past, may use “Thou” and “Thee,” but they are using the only intimate address their language ever had.

How much have we lost, when the address for loved ones and for God seems so old-fashioned it makes us laugh?

It really is fascinating to speak a Romance language and experience for the first time the shift from formal you to informal you and the meaning contained therein…the closeness it creates, the feeling of friendship with the other person. And also the reverse, the shock when someone uses the informal you when it’s not appropriate. We have other ways of doing this in English (calling someone sir or dude or buddy or some other word), but it’s not quite the same.

Well said. When I see people writing that their 'favourite words' are multi-syllabic, often Latin-derived, often made-up words, I remember that the most beautiful poetry (I think) in our language, Shakespeare's sonnets, are often composed of words of one syllable. Nothing against our Latin-French heritage either, of course I love that too, but English packs a lot of meaning into those little words.