I know I’ve taken a little bit longer to post this time around, given the wild whirlwind of the last two weeks, and given my own busy life. I want to say a lot about politics, assassinations, abdications, Brat Summer, etc., etc.—I’m tempted to even as someone exhausted by the dramas of Substack takesmanship. But I’ve been delayed working on a longer piece for publication, as well as a piece of maybe-semi-pseudo-takery which will likely end up here. So you’ll have to wait a little longer for any commentary from me! In the meantime, I figured I’d take a second to thank everyone who has been reading, sharing, and subscribing thus far. It means a lot.

So here’s something new for the week.

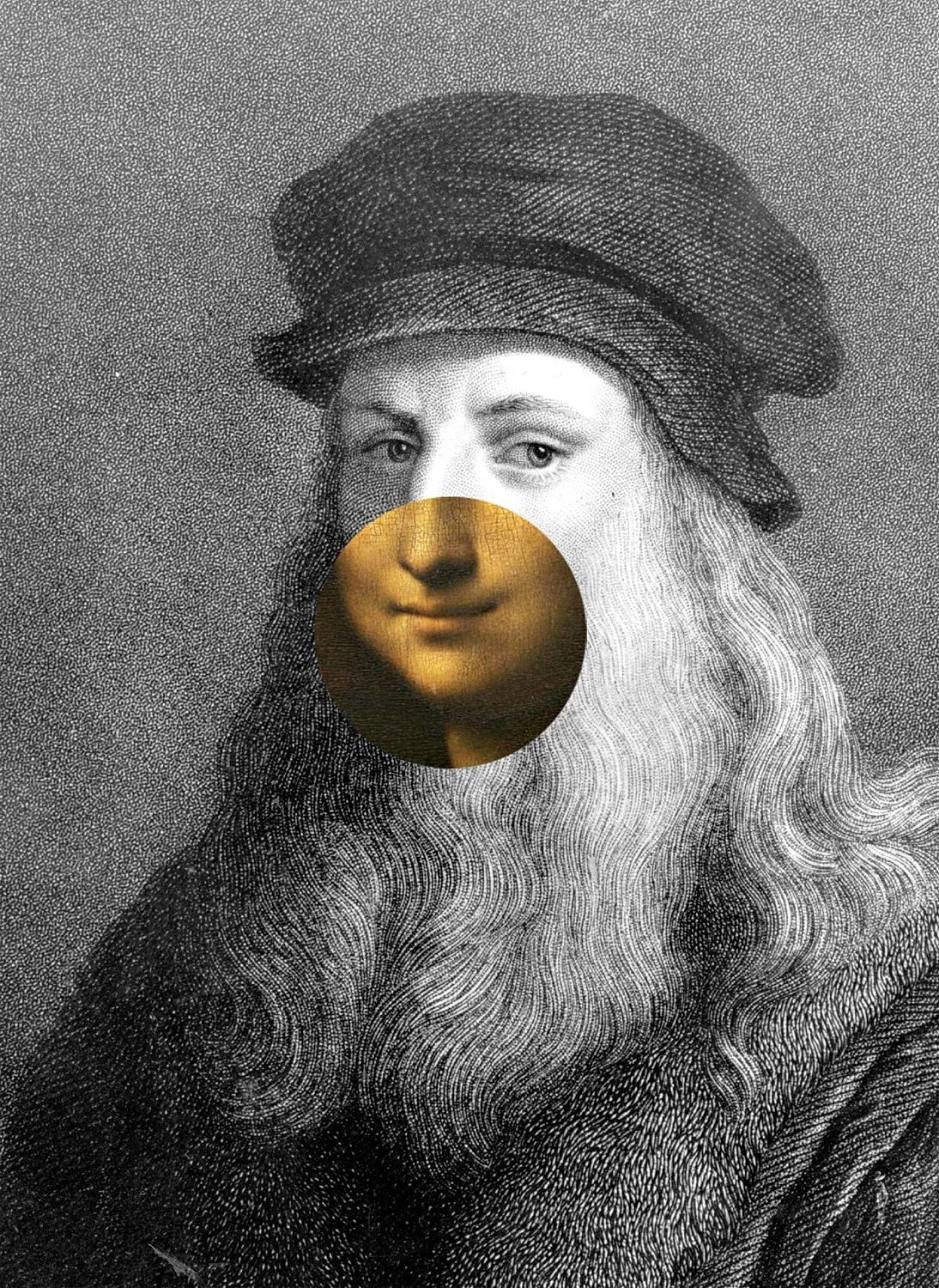

It was 2079 when they finally woke up the artist. He had been dead for 560 years. It had been very peaceful for him.

For a long time, this was deemed impossible. The artist’s tomb at Saint Florentin in Amboise had been destroyed during the French Wars of Religion, and the church itself lost later in the Revolution. Napoleon had supposedly searched for certain resurrecting talismans in Egypt, though they were still of no use: the artist’s grave wasn’t found until 1863. Since that time many had tried to revive the bones believed to be the bones of the artist. But it was all to no effect.

It was a team of strange, rodent-like men that finally did it. For decades, they’d worked in their lab (a secret, unknown subsidiary of TESLA), toiling at their Exhumation Machine. After bribing the French government with special access to their pan-human DNA database, they’d at last obtained the remains of the artist, such as they were, and brought them back to the lab, somewhere in the abandoned desert ruins of Phoenix.

After much tinkering, their Exhumation Machine finally worked, reconfiguring the artist’s body from his bones, extrapolating his complete genome. It took an entire year of laborious re-engineering. But the day finally came, and there was not a dry eye in the place: each and every rodent-like man understood that he was witnessing history, the first genuine revival of the dead. And soon a message was beaming in from Mars, where the preserved brain of their great founder still ruled, in exile, over his neural colonies. The men were to speak to the artist and show him everything that had happened since his death. They were to show him all the most extraordinary things mankind had ever discovered or created, and watch him marvel at humanity’s progress.

Immediately, they began to question the artist, to see if he would answer. He did, but in a language few of them had ever heard. One of them thought it sounded a little like an opera he’d learned in his youth. They ran it through their newest large language model, which could recognize most of the artist’s fifteenth-century Florentine dialect. But though it had access to any and all literature of that time, it could still only make guesses at some of his spoken language. Eventually, the artist grew frustrated, observing that these rodent-like men clearly didn’t know his language. He tried fifteenth-century French, but the effect was much the same. Eventually he tried Latin. None of the rodent-like men seemed to understand that either, but at least their language model could translate it with far greater accuracy.

The artist, clearly impatient to return to his rest, asked the rodent-like men what they wanted from him. They explained that they wanted to show him all the extraordinary things that had elapsed since his death. He responded by asking whether, after observing everything humankind had discovered and created, they would then let him rest again, and return to the bosom of the deity. They conceded. But in their hearts, they still planned to keep him alive.

First they showed him the Exhumation Machine. They explained how long it took to build—then they explained how they used it. The artist seemed unimpressed. This was something he had seen himself, he explained: he had watched cadavers stand up from mortuary tables, heard of supposedly-dead people clawing themselves out of graves. Besides, the Savior had resurrected men in ancient times, and there were stories of saints doing much the same.

The rodent-like men were confused. They asked the artist if he really believed this. He answered that he did. They insisted that most people no longer believed in such things. But the artist’s answer to this confused them so much, they started to think their language model might be mistranslating him. It sounded as though the artist said that this must be why they’d spent so long building their machine.

Next they showed him pictures of airplanes and rocket-ships. They tried to explain Calculus and Quantum Theory to him. The artist was more intrigued by these. He was even able to pick up on the basics of flight, and some advanced thermodynamics, after much querying of the language model. They explained germs to him, and electrons, and DNA, and photography. And indeed, he did find these fascinating. Approvingly, the artist remarked that they deserved to feel much pride for discovering so much of the deity’s incredible designs. The rodent-like men were confused again. These discoveries had shown them how unlikely it actually was that there was a deity. Merely considering the size of the universe, and their minuscule planet, they asserted, would demonstrate as much.

To this the artist didn’t say anything at all, but smiled to himself. When they showed him their machine for beaming live digital screen-capture from the lab to Mars, they saw that the artist had clearly begun to grow tired. The rodent-like men insisted again that this was an unfathomable technology, that the artist should be amazed that they could send such images from the Earth to Mars, and in only thirty minutes. The artist agreed that it was indeed very remarkable. But still, the artist didn’t seem impressed enough. He asked them how many more things they wanted to show him. Then, as if briefly inspired, the artist asked them who among them was an artist like himself. None of the men were, and when they explained that there were few artists anymore, that they used computers to make most things for them, the artist seemed very sad. Then he asked, begging their pardon, whether this meant the rapture had already come, and whether the rodent-like men were the ones left after the rest had been taken to heaven. Then the artist wondered whether he himself had perhaps been denied heaven, on account of the handful of times he slept with boys.

The rodent-like men insisted that the artist was speaking nonsense, that there had been, and would be, no such rapture. The artist looked as if he didn’t quite believe them. So again, they showed him a machine, hoping that this one would finally excite the artist. And it was an extraordinary machine, one which could perfectly paint the artist’s masterpiece, the Mona Lisa, in only a few seconds. They demonstrated it for him, yet the artist was still not impressed.

Again, the rodent-like men insisted that the artist simply didn’t understand how miraculous it was. Here was his great masterpiece, done flawlessly in a matter of moments. But the artist’s answer to this confused them even more. And if they weren’t quite sure before, they were now fairly well convinced that their language model was not correctly translating him, since the model rendered his response like this: “Miraculous?” the artist seemed to say. “What about this is miraculous? All I see is that it has taken half a millennia, and the efforts of thousands of men, to perfect a technology which can do what I was able to do by myself.”

At this point, the artist began to demand in earnest that they let him return to his rest. The rodent-like men, astonished by all of this, began to feel it was perhaps best that they do so. Using the Exhumation Machine, they undid their work, reducing the artist again to his decaying dead bones. They sent messages to Mars, asking what to do afterwards, and it was agreed that they should return the bones to their natural resting place.

It was then decided that the Exhumation Machine would be abandoned, and that none of the findings would ever be made public, to save them any future embarrassment from the alarming close-mindedness of more dead geniuses. Such people would clearly never be sufficiently impressed by the power of the new technology, and therefore had no real purpose for the rodent-like men. There would be no more machines like the Exhumation Machine. Instead the rodent-like men decided they ought to set their sights on developing another new technology, and they thought for a while about what it could be. Then they settled on one they hoped would, with enough tinkering, do something remarkable, enabling them to send messages to Mars in twenty-five minutes, instead of thirty.

I thoroughly enjoyed the fable tone. The simple characterizations, shorter sentences, and the intentional lack of specificity, made it feel almost like an oral recounting. Some very funny moments as well. I do have to take issue with the artist asking about the rapture, though. The rapture wasn't really a thing until the early nineteenth century. Still, a great story.

This is brilliant and I’m so happy I came across your writing—I love how you characterized the artist’s gentle, patient skepticism about all this futuristic technology. Genuinely such a pleasure to read