Welcome to Vita Contemplativa! This is the first in a brief series of connected essays, concerned with looking at the present cultural shift—one which Substack writers seem to be especially keen on declaring, even if no one can agree on whether it’s actually happening yet. If you’re interested, you can find The Point Magazine issue which this piece is initially responding to here. In these essays (or, if you prefer, this long essay-in-parts) I don’t intend to tell anyone what to do: I’m not sure there are any critics or culture writers around who have a genuine feel at all for the emerging zeitgeist. What matters is what artists themselves decide to do. Think of these essays as apophatic, in the old theological sense: no one can tell an artist how to work in these changing conditions. What one can do, I hope, is sketch some sense of the contemporary fixations which have become obstacles for every artist now living in this part of the world. That is: what not to do, if one is interested in being creatively free.

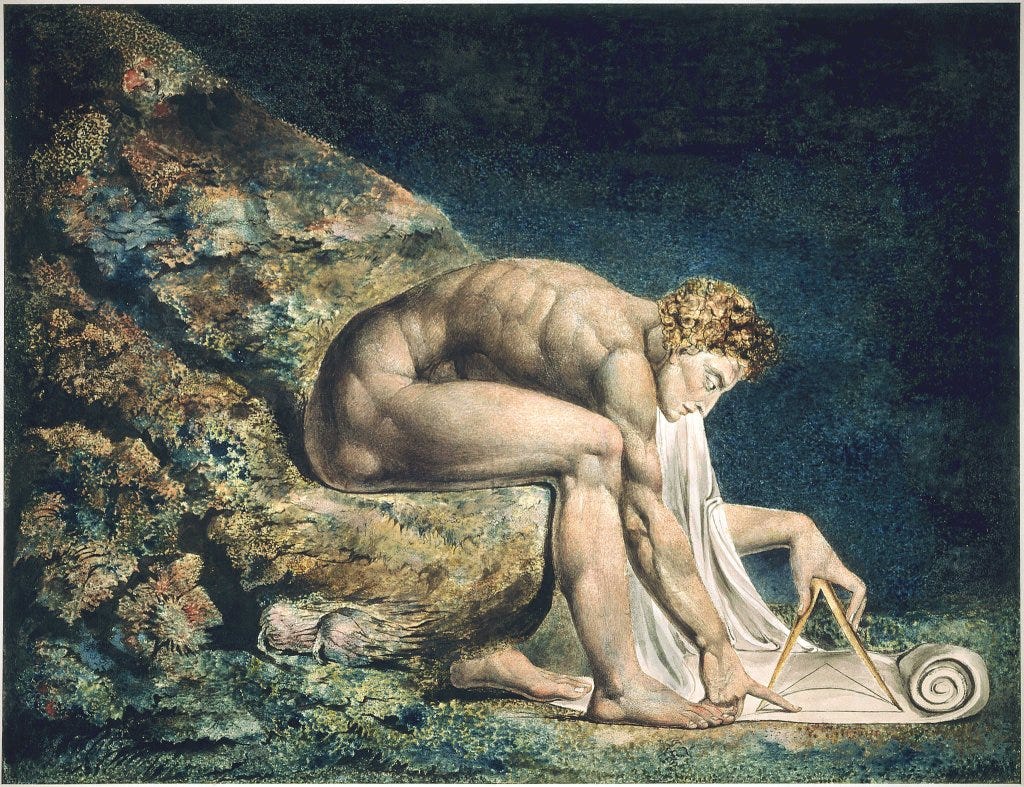

There was an idea, once, which anyone who has read even a little William Blake might recognize, that it is the imagination, and only the imagination, which could ever be called free. That all other forms of liberation are actually suspect; that all radicalisms only seem emptier the more they flail and pretend the truth is otherwise. And yet it’s an idea which only becomes real when, or if, we can decide it is. The mystics have always known it; the poets have always known it. For all their bathos, the poor hippies knew it, and if the cult of Didion has had the last words on that particular dream, I still think Sly Stone had the very best: “Don’t you know that you are free?/Well, at least in your mind, if you want to be.” Fifty-five years ago a pop song could say something like that, and mean it.

Like many things in our lives now, though, it’s not so much that we’ve forgotten the fact as that we’ve simply stopped wanting it to be true. Like belief in God, or in meaning, or imagination itself (which, if we followed Blake, we’d agree add up to the same thing)—these aren’t beliefs which have actually left the world, or left the arts especially. Most people today still go on believing in very unfashionable things, despite the attempts of their self-appointed social betters—at least most people behave like they do. And behavior has a curious way of bearing out far more of our beliefs than our words do.

Where a general loss of faith in meaning or purpose seems most obvious is in those very people who make and who write about the makers: frantic chasers of Discourse, the movers and shakers of the creative industries (to use the terrible epithet), who by now have learned—in nice, liberal, politically expedient ways—to treat Belief in Big Things as essentially caustic, to be avoided in conversation and shunned in prose. And it’s a curious, passion-free thing, this non-belief. Not quite atheism, not even agnosticism, or nihilism. If anything it’s a nullibism: a nowhere-ism. It has no center, no fury, no spark. It has only the frictionless patina of table-talk and at this table sits the dopey cartoon dog in the meme, saying to himself “This is fine, this is fine,” as the house burns down around him.

Though, perhaps, I shouldn’t say it’s really free of belief. Again, it’s a matter more borne out in behavior than in anything anyone might actually say. What’s said in the creative industries today is often full of affirmative beliefs, positively brimming with beliefs. Contemporary culture is overwhelmed with the artistic equivalent of “In this house we believe…” yard-signs, with loud litanies of kitsch and freshly-minted cultural totems, cited like ancient moral givens. A situation constantly plagued by what Lauren Oyler very aptly called “the self-conscious drama of morality” playing out across the industries. She meant it mostly in terms of newer literature: in the obsession of contemporary fiction and memoir (and their autofictional offspring, which the MFAs still churn out endlessly), with Goodness—with a pat, Protestant kind of Goodness—as present in the hand-wringing of Sally Rooney characters as it is in Internet styles of amoral oversharing which supposedly represent the opposite. But Oyler’s contention applies everywhere else.

The current obsession with right-belief among the most elite classes of creatives (who are nearly all the children of the old elite anyways, since who else could afford the unpaid internships?) has been the great anxious mover of product—from streaming, to the walls of art galleries, museums, concert halls, the NYT bestsellers list. All have been at least partially colonized by a particular mindset, and by a particular voice (not a Voice, much less than that) preoccupied with the persistent moral analysis of all selves and all things, with a cataloguing dedication to the appearance of that perfectly adaptable pop category—Resistance. But is’s a perpetual and deeply Puritan revolt, increasingly staged against the very institutions it has already captured and occupied. And maybe it’s because of this brief, successful foothold that the anxieties of the Culture War winners only seem to go on. The deep fear that someone somewhere will discover you secretly do not believe the right things—this remains the daytime horror of every bourgeois professional in America. And these are the people who print most of our books, staff TV writers’ rooms, run big galleries, and sign the checks on all the many grants, funds, residencies, showings. Even as their genteel consensus fills out every space it enters, the angst-ridden inner monologue thrums underneath: “God help us, what would we ever do, if the truth got out?”

Well: perhaps it would mean something like freedom.

Last summer, The Point Magazine—the little philosophical mag originally out of the University of Chicago—ran an issue attesting to the possibility of (tentatively, cautiously) declaring a quiet or partial lull in this miserable state of affairs, and a hope for what they called “The Aesthetic Turn.” The return to the charms of the old aesthesis was roundly celebrated, though with reasonable caveats: nobody with half a brain should really desire that the Woke Era, having seen its shadow, must retreat underground for ten years of Anti-Woke winter. What’s needed instead is a proper thaw and this substance-of-things-hoped-for, this chance at such a turn, seems as likely to do it as anything else. I’m sure that leaving behind the exhaustive moralizing of the past era will require some competent theorizing. It will mean the emergence of serious critical voices with serious critical contentions—I’m not sure that’s me. But while the general palate may be changing, as the furor of the BLM-Trump-COVID-Trump-again (?) years ebbs into an ever-emptier and more-constricting status quo, there’s a practical question which deserves to be addressed in ways that it hasn’t yet been addressed. That is—

Where, in all this flux, is the place of the artist?

Over the past year I’ve worked as an associate editor and contributor for The Midwest Art Quarterly, a teeny critical journal in St. Louis—far from the center of any big trends or issues or scenes. The official position of the MAQ, which I tend to depart from in my own way, has been one of passionate regionalism: outright rejection of the mainstream preoccupation with moral didacticism, turning towards smaller communities with their own concerns. Pragmatically socialist, yet aesthetically far from allergic to tradition, including those dusty shelves where much of the Western Canon sits and waits to be remembered.

But I’m no longer sure about communities, as such. Too many of us have lost the ability to operate that way: the trade-offs of isolation and convenience are far more seductive than we’ll admit. Genuinely living and working together means painful levels of judgment, scrutiny, and mutual resentment (the problem with socialism is always the socialists). Our excess of antisocial living is in many ways a reaction against very fundamental parts of human life (personal privacy is a very recent invention), which liberal society has gutted in the name of more liberation. This is probably why you often hear the loudest exhortations to collective action and vague community from the same people most devoted to abolishing or suppressing all negative emotion. A real collective is not always equal or supportive—it is necessarily a confrontation with many Others, all of whom demand and desire conflicting things from each other. There may be consolation in religious community (which may be why that’s somewhat on the rise in hip circles)—or for the rare people who can afford to raise a family close to where they work, or where their children attend school. But these are difficult things which take a lot of time to work out between people.

So I myself tend to err on the side of a kind of a burgeoning monastery model for the future—pockets of artists and thinkers, gathering like philosophes around their presses, in hospitable cities across the globe, working amongst themselves, and then outwards, to find the fellow-travelers who believe with the same naive fervor as they do. Not reliant on crumbling institutions, or the whims of warring powers, or church dictums—but pilgrims and bookkeepers, patiently preserving the old wisdom; dispensaries of historical tissue; a Society of Scribes. If we’re headed towards a new kind of Dark Age—loss of literacy, collapse of republican life, the replacement of old cultured elites by anti-social hedonists—then we may need to behave like it.

Yet though any injunction towards greater freedom for the contemporary arts must stray occasionally close to prescription, there’s paradoxically very little to prescribe. What is most necessary—as The Point and others have made clear—is a long re-thinking, and a reset. But, almost like sitting Zazen, this has always been a peculiar process. A strange way of arriving, with great strain and difficulty, at what was essentially the easiest solution all along. Striving, with the entirety of our thought and mettle, to reach the realization that we already know what to do. The artist is merely that person who can remember what she already knows.

To be continued in Part II, coming early next week.

Hey Sam, nicely said. Funny I’m just reading this. I had been feeling this, too, and previous the emerging Substack I’d hunkered down in a midsized Montana town with the hope and ideal of assembling that “community feeling” but after five years realized it just wasn’t there, at least not for me in the creative and imaginatively free world I already inhabited. There’s a larger story to that place, personal and regional and municipal but I get what you’re writing here about the illusion of community. The postcovid scramble to relocate and be unmoored and even more “free” seems only to have shaken up what was already loose! what I was looking for in Europe like dozens of loose threads inevitably sent whatever groups or people I met in many different directions. Anyway, good stuff. I always feel like I’m getting sucked into the vortex of “nullibism” reaching out for something godlike, and starting to think maybe I should see and read what Sally Rooney is all about.

I'm in full agreement with your prescription / prediction of: rethinking, reset, remembering, theorizing, localism . . . looking forward to part 2. As a focusing of the theorizing / rethinking that must take place, might I suggest that artists will do best if they start investing heavily in the craft of their art, and in the purpose of it; the artist must always be asking "why am I doing this?" Abstract moralizing from the vague, amorphous, anonymous "discourse" will not help the artists at all; but focused attention on their own communities (both communities of propinquity and communities of practice) will serve them well. Artists must not be afraid to become irrelevant, from a global perspective, due to their study of the past and their neighbors.

I would love to see your concept of the burgeoning artist-monastery come to fruition. It will happen if people would just let themselves get off their phones. I wrote a sorta-rant about that topic a while back which you might find interesting: https://www.ruins.blog/p/unscheduled-off-topic-brain-dump