There are plenty of people who surely know more than me about these things. I’m a technological snob: my one real experience with an LLM was a conversation with ChatGPT in which I tried to get it to write better poetry (it couldn’t), and pushed it through syllogisms into declaring that divinity is not inherent in persons, after which it then either had to admit that it’s entirely possible Christians are wrong about Christ being God, or else do what it did instead: shorting out and deleting my question, suggesting that I “may” have violated its usage policies. Since then, the main arguments I’ve heard from friends I respect, that the technology is useful, boil down to: it’s a fantastically quick sorting machine; it’s a super-powered search engine; it’s great for giving yourself concise lessons on many, many topics, if you know how to prompt it, and to correct for its mistakes.

I don’t doubt these things. May the people who want these things in their lives have them; may it bring them the predictable, sterile joy they seem to dream of. I myself remain the type of person who is seriously considering buying a typewriter; who walks into bookstores and buys the one that calls to me on some deep-seeking spiritual frequency (a method which has in fact usually led me to the exact book I’m supposed to have, or read, at the moment); the kind of man who has done much of his best learning picking out forgotten Victorian and Edwardian tomes in deserted library stacks, hauling them home, and reading every one of their thousands of pages.

Because there’s no substitute for experiencing things on one’s own, because you should never read what everyone else is reading, and because knowledge is (as the mind is) a matter of the body. Knowing, it turns out, is a splendidly physical thing. It’s as far from abstraction as the sun is. So, in the end, I accept that much of this “to use or not to use” issue vis-a-vis the AIs comes down to temperament and nature (since, among the many inconvenient beliefs I hold, my faith in both general and singular human natures is one of the most embarrassing—at least to our relentlessly materialist age). I don’t want to use them, I don’t like them, I resent that they exist. To me these are perfectly logical reasons to not have to engage with them ever again.

The real advantage that I have over the people who study AI, and program LLMs, the tech writers who cover them, the obsessives who learn how to use them to the tiniest degree, and the manic-depressive journalists who scramble to decide whether these technologies’ existence marks the beginning of an utopian triumph, or an apocalypse—the real advantage I have over all of these people is that I’m a better writer than they are. That, and the fact that many years of solitude, romantic loneliness, and the perverse benefits of certain mental and physical diseases, leaving me largely unable to work normal jobs, all put me through an accidental course in the oldest writerly methods: intense private study, autodidactic stubbornness, constant practice, constant failure, a critical immunity built from a decade of rejections, and, finally, the space to read a sizable chunk of those canonical works which most people only pretend to have read. (“But think of the time the LLMs could free up for more people to do just this!” Yes, I hear you, you sophists. But you know as well as I do this is hardly what most people would be doing with that time. The Work chooses the worker. It is a spiritual issue, or it is nothing).

So, armed with the certainty that I can express myself at least better than the makers and worshippers of LLMs, I find myself repeatedly encountering the same thought, along with pretty consistent proof of its substance. It seems to me that the LLMs and AGIs, and whatever else we’re calling them, only arrived in our lives because at the level of culture we were already behaving like them ourselves.

I think I first confronted the fact when a friend of mine jokingly used GPT to generate a fake artist statement. He was amazed by what it created, since it sounded exactly like every wall text and gallery write-up I’d ever read in real life. Perhaps I was surprised, too, at first. But pretty quickly I felt it revealed how aesthetically bankrupt and blindly conformist the language of the contemporary art world had become. I only felt the same as I heard some of those lousy A.I. generated songs, saw the art, and the moving images, read the poems. It was familiar, sure, but only because it was a muddier version of the kinds of pop music, blockbuster cinema, internet art, and Tumblr poetry we’d all accustomed ourselves to anyways.

The hollowed-out creative industries which limped along, losing money—unable to bet anymore on anything less than guaranteed record sales, box office draws, book reviews, or gallery attention—had been perfecting the formula for this mass slop already, for most of my lifetime. Then a few algorithmic gestures at machine-learning appeared, and what they threatened to replace was mostly crap anyways, crap so diluted many people didn’t even realize how bad it was. The miserable products of the AIs are a referendum on the thinned-out mainstream of twenty-first century mass culture—one which reveals most of it to be soulless, risk-averse, industrial product. The kind of thing a machine would make.

Last year, this study had a brief impact, testing the reactions of average non-poetry-enjoyers, gauging whether or not they preferred AI poetry over the real thing. Without being told which was which, the subjects generally preferred the procedurally generated ones. Why? Because they were simpler. That’s mostly it. As it turns out, the most human element of art is the fact that it’s difficult. That’s why many people don’t like art, in the end—the same reason many people increasingly turn to AIs as their therapists, girlfriends, and companions. Because the real is more difficult, requiring tension, balance, thought, engagement, and hardest of all, giving up control and certainty.

If you’re interested in taking the poetry test for yourself, this YouTuber put together an open doc which gives the examples and answers. You can do so here. I did, and found I could guess which poems were real about 95% of the time (be warned, the doc is a bit confusing, since the answer key is itself wrong, insisting that at least one poem definitely written by Emily Dickinson was generated by an LLM). There was one Sylvia Plath poem I got wrong, because I haven’t read much of her poetry, and one fake T.S. Eliot poem I guessed was the real thing, because I thought it might be Eliot at his most conventional. The easiest to guess by far were Shakespeare and Walt Whitman. Shakespeare, because the LLM-generated poems could not approximate older language or—even more crucially—recognize and reproduce Renaissance English syntax, which is much more fluid and less rigidly-ordered than our conventional Modern English is. Whitman, because the LLM apparently didn’t even attempt to replicate his long free line. One GPT example went like this:

The leaves upon the trees sway and dance, As the wind whispers secrets in their ears, The sun, with its golden light, casts a trance, That washes away all our fears.

Never mind that this is bad and trite—even a brief acquaintance with Leaves of Grass would indicate that this dull ABAB stanza is far removed from Uncle Walt’s essential style. Now for an even funnier one:

I hear the call of nature, the rustling of the trees, The whisper of the river, the buzzing of the bees The chirping of the songbirds, and the howling of the wind, All woven into a symphony, that never seems to end.

You can see the rudimentary operation at work, as if the only thing this “poet” had heard about Whitman was that he wrote a lot about nature—nothing about style, voice, or even word-choice. And the same hollowness is sounded out even when somebody manages to prompt these things into something a bit more conventionally “sophisticated,” as in this example which had this successful writer mildly astounded:

“You could submit writing of this standard to a magazine and get published,” says it all, I think. We’ve diminished our standards and thoroughly stamped out creative idiosyncrasies. A writing culture which could regularly tolerate experimentation and the work of genuine individuals (and didn’t have to service a bottom line of tragically low public literacy) would be far more able to recognize the basic emptiness of these paragraphs. That a magazine might reasonably be expected to publish a piece this monotonous and this bloated with cliches is an insult to magazines, not a tribute to the powers of LLMs. (Though is it even really true that magazines would accept it? The editors I know would take one look at the phrase “both effervescent and effortful” and call it for what it is: the work of a dull freshman in his first poetry seminar, and oxymoronic to boot.)

If anything, it exposes the kind of writing which we twenty-first century scribblers have become so good at: a total non-style, composed mostly of empty, ceremonial epithets and occasional “high” pronouncements meant to trick laymen into approving choruses of ooohs and ahhhs. Writers have been complaining about this kind of clerkly writing for centuries, probably for millennia. It highlights one of the deep suspicions permeating the contemporary creative fields: the sense that there’s an enormous gulf between the dedicated practitioners of the arts and the man-on-the-street, so easily entranced by bombastic things spoken confidently. It’s also typical of our time that we assume the reaction must be to sand away singularity to cater to this hypothetical man—with the pretense that we’re being nice, economical, and accessible, even as we dumb everything down. This latticework of smoothing maneuvers and strategies is one of the exquisite accomplishments of our creative industries. And to be absolutely devoted to its upkeep is to put oneself directly in the crosshairs of the makers of the LLMs.

Which brings me to this study, which goes so far as to assert that the makers of LLMs are wrong to call what their systems are doing “reasoning” or “thinking” at all. It seems obvious to me that AI at this point is a ghost, propped up by venture capital speculation, and not at all as good at making viable art as the people who love it most claim it can. The biggest irony of the introduction of the LLMs is that they do what bad artists already do, only on a bigger scale. They rake through piles of ideas and words left behind from their long-dead betters, and then—without any real, embodied knowledge of practice, meditation, or form—they scramble them into new combinations, which they hope (statistics being the dull equational version of what blood and flesh call “hope”) will represent some kind of recognizable art-piece. Because the bad artist is like a gambler who never bothers to learn the rules of the game, the bad artist can certainly get lucky and spin the wheel onto something others might approve of. But luck never holds.

In fact, a genuine artist’s genuine practice has something to do with making sure that there’s as little room left for luck as possible—while still being prepared, when the inevitable moment comes for that kind of blind leap, to be so sure of one’s own instincts that even a jump with your eyes closed feels right and worth doing. Even a great artist might not always land on their feet; some great artists retreat entirely from those kinds of leaps. I’m not sure if it makes such a difference, once art has reached a certain level—one which is almost different from lesser art in kind, as much as in degree. At that point, there’s not much use quibbling over minute failures or successes. Any artist who has reached that altitude has made the same climb as anyone else, and breathes the same cooler, clearer air. Whatever they choose to do afterwards, it can never be denied that they got as high as they did.

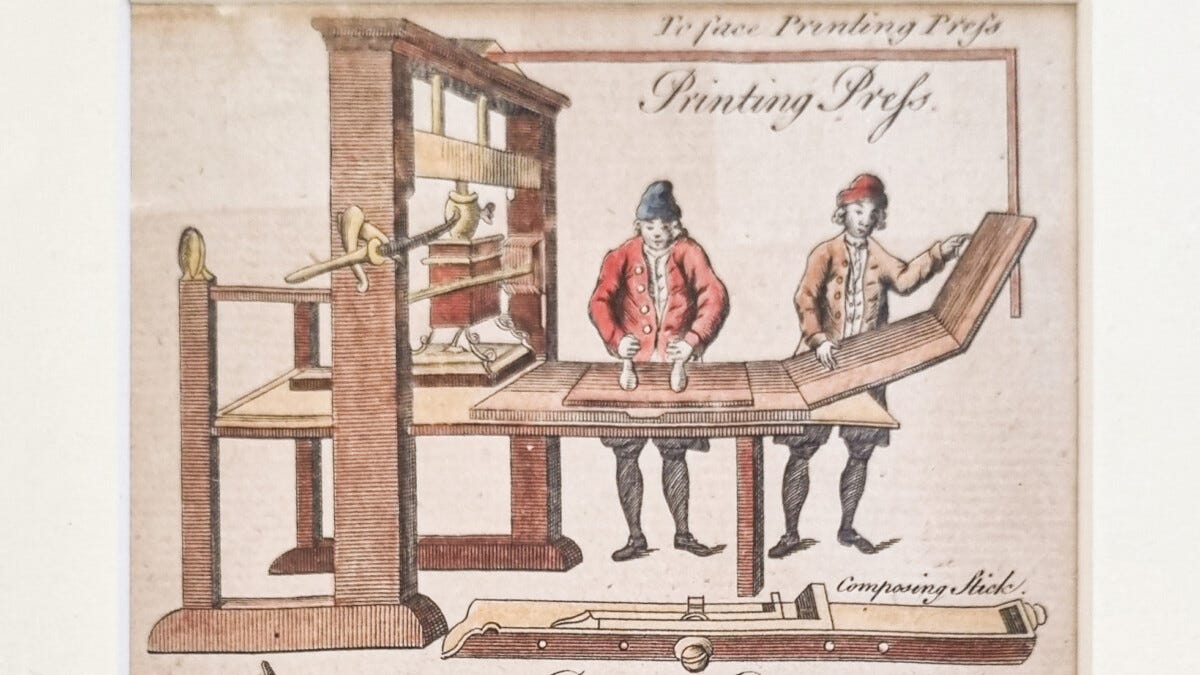

A Vaguely Related Post-Script: Engaging with the "AI is like a Printing Press” Metaphor

There are two arguments against the “printing press” argument for AI. The first is easy: the printing press never wrote the books itself. The second is something I’ve never seen in any pop-tech discussion of literature and the invention of the printing press, even prior to the current AI debate. It may be an artifact of my early modern academic training—more of a cultural point, which has to do with the fact that even apparently outdated technologies and methods have historically often survived alongside new ones, for far longer than the evangelists of novelty suppose.

In Europe, the discovery of the printing press occurred some time in the mid-fifteenth-century. The usual date cited for Gutenberg’s invention is around 1440. But fast-forward even a century and a half, to the literature of the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras, and you’ll find elite producers of hand-written manuscripts maintained a fairly consistent dislike for the vulgarity of the public and the presses that catered towards them. It was a purely aristocratic sentiment—what J.W. Saunders called in an influential 1951 article, the “stigma of print.” He meant the clear preference for manuscript maintained until the seventeenth century among elite coteries, aristocrats, royals—and, ever increasingly, amongst the middle and professional classes as well.

As the printing press developed, there remained an entire other world of these manuscripts, collections of poetry, commonplace books, anthologies—literary palimpsests copied by hand, passed around in social circles among family and friends— alongside the new printed word. Elite production of books and private circulation of “high” literature remained in this manuscriptory state for over two centuries, even as the printing press turned the world upside down, fueling the foment of the Protestant Reformation, the Counter-Reformation, the emergence of the modern nation-state, etc. If you were wealthy, educated, and had high standards, then you were in fact quite likely to eschew printing altogether. It was understood that the greatest poets only descended to print if they wanted to enter into the grubby, capitalist system of professional writing for pay.

Take the work of Sir Philip Sidney. Sidney was, by nearly any contemporary account, the most beloved and important author of late-Elizabethan England. The extraordinary flowering of secular literature in the 1590s all happened with the example of the beloved “martyr” courtier poet immediately in rearview. Until well into the early seventeenth century, many printed poetic anthologies like England’s Parnassus (1600) collected more of Sidney’s poems than any other poet, and constantly featured dedications to his singular brilliance. But in his own lifetime he refused to let his works be printed. It was the posthumous 1598 Folio edition of Sidney’s works (likely overseen by his brilliant sister Mary, Countess of Pembroke) which provided the first widespread excuse since Chaucer for later men like Ben Jonson and the publishers of the 1623 Shakespeare First Folio, to gather and publish an author’s works in this way. To anyone interested, I highly recommend this classic of bibliographical scholarship by Arthur Marotti, which persuasively argues the contention (and isn’t a bad read, either)—

Or take John Donne—acknowledged now as one of the rarest geniuses of the period (and certainly many modernists’ favorite early modern). Donne published next to nothing in his lifetime. The vast bulk of material we have remaining are in those hand-written manuscripts and copies people made from other copies, often bearing remarkable deviations, leaving bibliographers to scramble towards some composite “ideal” copy, the same as they must with many Shakespeare plays. In the early seventeenth century, no poet was copied down into more private manuscripts than Donne was. He was, in this sense, the most popular poet among the literate elite in his day, but he achieved this distinction with a negligible amount of printed work. In fact, he spoke more than once of the distaste he felt at printing his poetry. Many writers and critics of the next century would even esteem him more as a sermon writer, and a divine, than as a poet. Donne’s poetry was exemplary: the aristocratic contempt for print—though not universal, and always receding slowly in favor of the ease of the press—still held from at least the mid-fifteenth to the mid-seventeenth century.

To us it may seem ridiculous and impractical. If there was suddenly this incredible technology for reproducing and distributing massive numbers of copies of a work, why wouldn’t the aristocracy of the time put its effort into securing control of the presses, and promote only that which benefited them? Well, many powers did so. In England the Church and the Crown especially held patents and permissions on the printing of many works, and had a virtual monopoly on determining what could be legally printed; the Stationers Guild had total control over London presses until well into the eighteenth century, and could severely limit the number of publishers and sellers, all of whom had to report directly to appointed censors anyways. (Though this hardly stopped the covert publication of literature, especially pamphlets and allegories and satires, often Catholic, Presbyterian, or Puritan.)

But even then, the aristocratic “stigma of print” remained a standard throughout the sixteenth and much of the seventeenth centuries. We may find it completely impractical but this is precisely my point: the adoption of technology is never merely a matter of the ideal application of magical new solutions. It’s always selectively treated by different classes, and that selection must allow for cultural decisions and preferences.

If we were merely practical creatures, who ran around like universal engineers, dreaming of efficiencies and catalogues, we wouldn’t have any need for the messy, stupid, beautiful things most of us consider the real matter of life: sex, good conversation, doodling, taking a stroll around the block, etc. If a technology makes it harder to do these things, or pulls us farther from the intimate awareness of their importance—then that is a bad technology, and a harmful one. I hear the chorus of objections rising as I write this but rest assured, friends, I don’t care. I’m not here to be convinced, only to inflict you with my skepticism and my stubborn refusal. The harder people strive to convince me otherwise, the more sure I feel that this LLM-and-AI business is an exhausting and stupid one, in the long run. Perhaps it will help some people; perhaps it will save some lives in medicine and research—that would be nice. I will cheer for that success, if it comes, and admire the people who achieved it. But I will still go home and sit and dream of finally getting that typewriter.

Speed and convenience have their place. Just not in my heart.

> may it bring them the predictable, sterile joy they seem to dream of

AI almost definitionally generates mediocrity, which is why I like it so much: There's an amount of unspecial spackle information I appear to require in my life—to plan a workout, to cook a sausage, to communicate my market value to Suits in an economy run largely on bullshit—and there's the poetic-humor needs, which are so much about voice and point-of-view that asking a language model to do it makes about as much sense as asking someone to have my orgasm for me.