1. I don’t like this place but I don’t want to leave

I have no idea what I’m doing here. This summer I’ll have been here for a year, but all I’ve discovered in my time on Substack is I seem constitutionally ill-suited for Substack. My essays always seem to become metafictional letters to someone. My takes always turn to criticism of takery. I’d rather write poems and invent new books and experiment with style, but Substack appears ever engineered for other things. Besides, I’m in this game to be a novelist, songwriter, poet, playwright, what-have-you. Criticism, autobiographical essays, haut takes etc., only dilute imaginative literature in this context. Which is not to say criticism or essays are useless, or not worth having, only that they’re best when they’re closest to imaginative literature themselves.

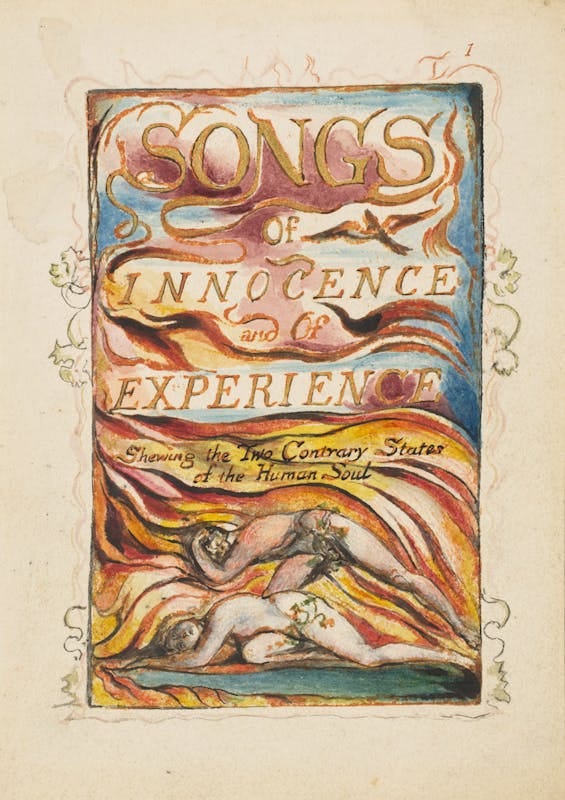

A week ago I finished reading Virginia Woolf’s Orlando for the first time, a book that’s so clearly the work of a genius, of a woman who discovered the most ecstatic inner freedom through her writing. It’s also one of the best pieces of indirect literary criticism I’ve read. It has more to say about the Elizabethan era, or the Long Eighteenth-Century, or the Romantics, than most books of more explicit criticism can manage. I considered writing about it here but soon found I couldn’t. It felt like a betrayal of myself, and whatever was communed there between myself and the divine Virginia.

Now the glow of the book still has yet to fade, and there’s nothing I can do to add to it. Any essay of mine would be reducible to two words: “Read Orlando.” Better yet, do it in quiet, in your room, alone. And don’t tell anyone. Keep the warmth of the experience tight to your chest, because that’s the real sustenance of imaginative literature, not the constant explication of its merits to strangers. For all great literature teaches us about other people, it teaches us even more about how to be alone with ourselves. Orlando, like Emerson, like Dr. Johnson, is not really for the classroom, let alone the Substack column. It cannot be taught or extolled upon. It is, simply, to be read, internalized, and loved. The only thing I could ever do to add to Woolf’s achievement would be to write a novel of my own, something aspiring to rise to Orlando’s height, however difficult that might be. To try to meet the generous challenge which her spirit offers us, across time. The Internet just gets in the way; the digital world creates too much fog, distraction, and distance.

There are surely dozens of similarly abandoned pieces somewhere in the digital trashcan of my Substack. Very often I’m moved by agitation to take to this space and blog and blog in one long screed—to engage in some little spat, to weigh in on the discourse du jour. But I always (always) find myself doing exactly the things I dislike in other polemics, or leaving myself open to a thousand possible charges of hypocrisy. The good news is that my readers are self-selected people with sincere interests and a desire to engage with what they encounter. When people comment, it tends to be kind. Though some large part of this probably comes from my never really writing anything too controversial, and mostly staying away from the land of takes, or declarations of concrete political stances. So I’m going to change that for a moment, in my way, if only to take myself somewhere else entirely.

2. Politics

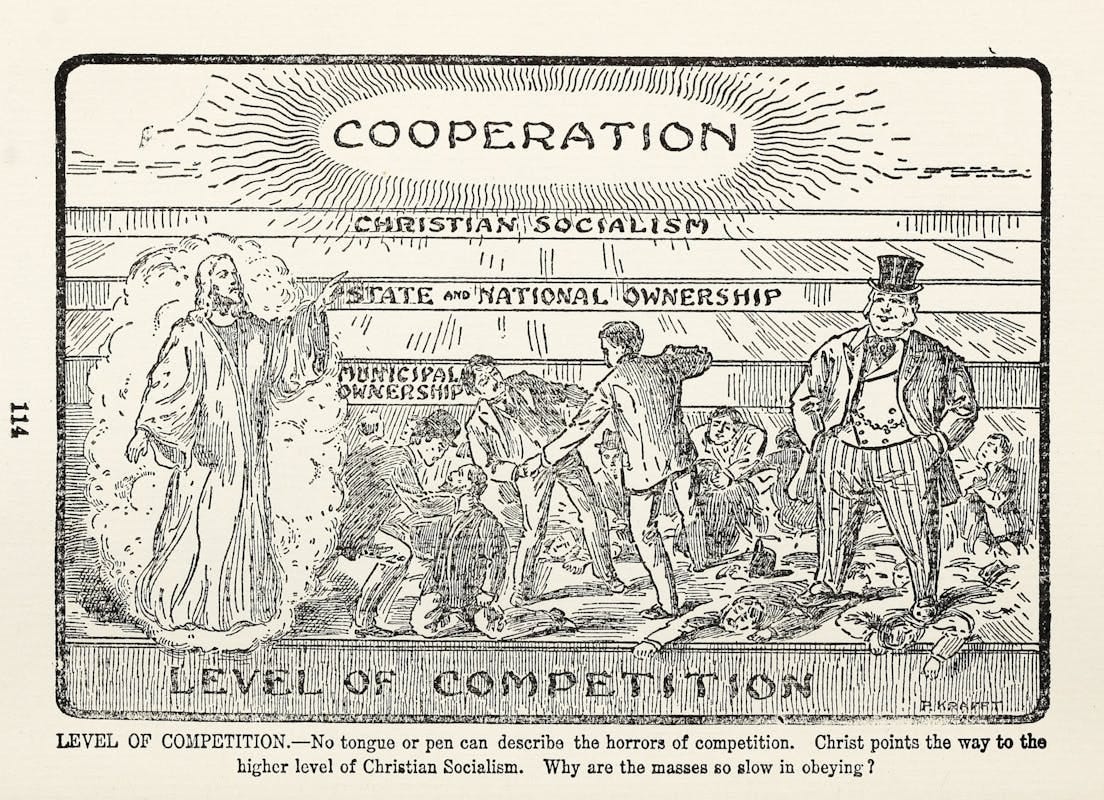

I will probably be a socialist as long as I breathe. I couldn’t tell you what I mean by that, exactly—only that it sounds right, and feels right, to me. I’d love for the rich to be taxed to hell, for poor and working people to be given every amenity a government can give. If any thinking person were to stop for a moment and consider other human beings and acknowledge that they are indeed real, I think they’d say, “These are my brothers and sisters, and our society is an immoral one unless it’s taking care of them. Until every child is fed and housed, until people no longer wander the streets, this society has no claim to being a just or a good one.” I don’t care a whit for realpolitik. Politics is about embracing impossibilities. Only once you know something is impossible does it become remotely possible to change it.

However, I’m also a species of conservative. Conservative in the sense that I believe in the sacrosanctity of roots. Roots chosen, adopted, inherited—it hardly matters. As Simone Weil said, there’s always a need for roots, and rootless people are often more of a danger than those more rooted are. I love so many traditions: American ones; European ones; East Asian, African, Middle-Eastern, Indian ones; Indigenous ones—amongst other unfashionable artifacts such as the English language, Humanism, the inheritance of the medieval universities, Buddha, Jesus, and the Dao. Even that big burden which is The Western Canon—I like that, too. Especially when it’s old and stuffy and staid, then it’s the greatest comfort there is for my beleaguered post-modern soul. I treasure all of these, and want to see every inch of them kept alive, protected from the kinds of civilizational and technological freaks who are always busy running around, tearing them down, calling it freedom. To declare this conservative feeling reactionary—merely a series of nostalgic traps—only reveals in the declarer a sad lack of imagination. And indeed, plenty of people (Utopians, Machiavellians, and Millenarians alike) seem to hate the idea of imagination.

But then there are probably a dozen things I could claim to be, any one of which is of much more importance to me. I’m a son, a brother, a friend, a writer, a student, sometimes a teacher, a musician, an artist, a man, a human, a soul or a fragment of a soul, a Cosmic Idiot, a Fool. Anyone of these gets closer to the nub of who I am, in my relationships to people dead or living, than any political designation ever could. And yet, true, I’ll still say “I’m a socialist.” If only because in the polity I wander and meet people, finding groups and institutions that puzzle me. And so far, in my life, it seems that the modern tradition which amounts to “socialism” still has on it the fingerprints of the best of our yearnings, our hopes for peace and provision. The word’s still got heft. It still means something, even if that’s something which might never be. It still sits up the way somewhere, waiting, as a worthy aim.

Yet there are conflicts. Like most people, I imagine, I also have my suspicions of contemporary progressivism and its weird cloud of implicit behaviors. For instance, I have an antipathy towards adults who talk loudly about how much they don’t like children; towards the played-out, vaguely-Marxist hatred of family; towards the patronizing idea that embattled ethnic or racial minorities need to be “liberated” into the correct politics and locked into a tokenized version of their own culture. I dislike whatever Wokeness was. On the other hand, this new right-wing application of the same petty register is odious, too. I would very much like to see Elon Musk drawn and quartered in the public square; I loathe the fascist cosplay, and the minions who have talked themselves into bigotry for the fun of it. As a devotee of the humanities, I especially abhor the use of tradition, canon, and classicism for the promotion of American Patriotism, excusing imperialism, or advocating for Christian Theocracy—all of which Republicans have been perfecting since at least the 1980s. Until someone finds a way to synthesize these broad strains and frustrations into a political platform which I could support, then I will be politically homeless.

There’s a very simple reason I’ve more or less abandoned all political commitments: I do not trust political commitments. I’ve seen how they make a wreck of people, watched ridiculous ideals turn the smartest people into the most narrow-minded puritans. Watched too many people I liked suddenly discover it was their duty to despise, judge, and assign whole swaths of their fellow humans to the dustbin. On my side of the aisle, it was astonishing, over the last 10-15 years, to see so many intelligent people decide that there was only one appropriate way of speaking (in that patented Tumblr-ish academic-therapeutic patois) which “good” people now used, insisting that anyone who wanted to do otherwise, or dared resent being told how to speak and think, was harboring a secret bigotry, and actually wanted oppressed people to die.

So I tend to no longer call myself a leftist. And indeed, if I look back at the long post-1789 history of the Left, I can’t help but feel that for every genuinely erotic revolutionary, there were always a dozen hectoring, policing commissars, with little compunction against hurting people. No: the most responsible thing anyone can do these days is to be constantly suspicious of any political party, institution, or movement. Even and especially when these happen to espouse politics that sound correct to you. The greatest discredit we can give to each other is to assume that being moral is a matter of suspending that instinctual suspicion, so long as we feel these are the “correct” parties, institutions, or movements. The good faith we ought to extend to other people should be in exact inverse to the mistrust directed towards politics.

It’s clear to me that most of the posturing in American (perhaps most Western) politics over the past 10-15 years has been largely a matter of discreet and harmful influence from above—that our supposedly “radical” politics were a matter of powerful people heavily invested in confining our public conversations to narrow channels. To the degree that people fell in line with ostensibly rightist, leftist, or centrist (or “heterodox”) dogmas, they surrendered their ability to think and reason to the equivalent of an algorithm (and perhaps to literal algorithms), whose greatest purpose was to divide, fragment, and keep us distracted. As far as I can tell, the people I know who survived this with their reasoning and sense of self still relatively intact were, for the most part, those who read old books. Not contemporary prestige slop—not Ocean Vuong, Ibram Kendi, Claudia Rankine, or the contents of Obama’s Year-End Reading Lists—but the good, solid, time-worn essentials. The literature of the past is always your best gateway to thinking for yourself, because anything you can do to pry yourself out from contemporary fixations is one further step towards spiritual freedom. You have to understand a lot of other minds and other times to see your own clearly—there’s simply no other way.

So the answer is not in Left or Right. The answer is not in politics at all. Let artists make a place for politics in their art, if they feel moved to do so—this is fine, normal, and human. But to stipulate that all art is political is a meaningless statement. It doesn’t matter whether or not we really even can have an art that’s free of politics. But there has to be a place where we might at least yearn for it. A place to experiment, to think outside of societal constraints and institutions. Is a coloratura’s perfect high E-natural political? Is a streak of paint? Or that gorgeous, frilly, almost ridiculous word “mellifluous”—is that political, too? Everything has a political context; everything is political. Very well then, I want my art to be political the way a mountain is political, or a tree: let it have its political resonances, insofar as it’s placed by an audience in one context or another; still it stands aloof, and is far grander and more beautiful, stranger and more suggestive, than any institution or society might ultimately grasp.

3. Gotcha!

On to the perennial problem with trying to get in on the take game: someone is always reading you with a net in their hand, ready to cry “gotcha!” as soon as they find an opening, pouncing immediately, trying to trap and castigate you. Substack, like all the internet, is aflame with paranoid reading, and therefore with paranoid writing. It’s our plague.

Last week, I was fortunate to be featured in the new Metropolitan Review, a publication I sincerely find interesting. But I saw, too, a bit of a backlash to the Review: a few self-appointed officers of snark even referred to it as the “Free Press Review” which legitimately angered me (as I assume it was supposed to). What Ross, Sam, and Lou are doing is earnest and very much needed, and I have yet to see anything other than that be true about their project. To compare this little network of writers to that nakedly cynical and politically duplicitous rag, or to suggest that the MR is doing the same thing, is itself cynical and duplicitous. It’s the rhetoric of people who still do not understand that the basic failure of the last decade’s progressive movements was to cede institutional critique to the Right. Now a new review comes around—with the stated mission of criticizing the establishment culture industries (MFAs, publishing houses, NGOs, universities; none of which ought to be above criticism), taking literature and art seriously without forcing them through any explicitly political lens—and some people are already quick to dismiss it is as right-wing. Hell, I’ve even seen Dean Kissick’s Harpers piece called right-wing, for having the rather lukewarm take that many art institutions have used an emergent cultural obsession with identity to peddle very dull, risk-averse art.

But these are tactics left over from the last frenzied, algorithmic epoch: you’re either championing progressive platitudes or you’re fueling the fascisti; if you think the current culture industries are empty and pushing crap art, then you’re on the side of the online trads, secret bigots, and violent incels. Do you feel like writing a rueful exploration of the pain of young contemporary women, and their occasional wishes for older kinds of relationships? You’re hardly allowed to expect a good faith interpretation of it. Want to write about the dominance of contemporary fiction by female perspectives, and how that might contribute to a shallow picture of men? There’s no way to do this without opening yourself to obvious charges of sexism. Perhaps I’m naive, to be so surprised by people who only see a criticism of the current culture industries as a conservative dogwhistle, but I really thought we were past this. I thought we all saw the way constant moral surveillance of one another only drives people towards anger, or indifference, or guilt. But then, I probably am quite naive.

Aren’t people tired of spending their time worrying about other people thinking the wrong things? This is just what’s been amiss with so much contemporary fiction: it’s been overly programmed to appeal, pruned of its edges, sanded of deeper character. Lauren Oyler (whose critical drubbing last year suddenly made me quite sympathetic towards her), in one of her finest critical moments, was as clear-sighted as anyone. She pointed to the ways in which contemporary fiction (like prestige TV, and so many popular films) has become exhaustively obsessed with what it means to be a good person. And still, after all that identitarian soul-searching, all that “empowerment” and “holding space,” we have ended up lost again in the cul-de-sac of narcissism. We’re left exactly where we began, with a culture incapable of bringing genuine, messy, humane art to the masses. It’s no wonder that the Alt-Lit thing, despite touting its ostensible messiness, has been (as Sam Kriss pointed out, and as I did last year), still very much ethically paranoid and myopically obsessive about private morality.

The constant gotcha!—the need to be always hunting out dog whistles, calling out hypocrisies—is one among many miseries of Substack. It’s the miasma of the comment section, the hell of the internet in general. The desert of takesmanship. We’re engaging with each other in constant bad faith, obviously and pointlessly posturing to signal to the kinds of people we want to be like—the only way to handle this is to accept that human beings are going to be fundamentally hypocritical, flawed, ridiculous; then to jump into the absurdity of human frailty anyways. I’ve said it many times, and I’ll say it again, this is the time of Fools. Only those who can totter blithely on, half-blind, shedding the last era’s political idiocy, will be able to make anything of value in a world of such increasingly sophisticated vapidity.

4. The Problem of Genre (The Culture of Diagnosis or the Diagnosis of Culture?)

A few things I do not understand about Substack:

Why people care so much about earnest, autobiographical essays. It’s not that immediate memoir can’t be good or artistic—but Substack is no glowing storehouse of wisdom. Any (I mean it: any) insight you might want to find here is something you could find in the treasures of the literature of past times, and in a less diluted form to boot. I sometimes suspect that part of the reason we turn towards the kinds of reading and writing which blogging tilts at by nature, is exactly to avoid having to encounter the real thing. Or at least, to avoid the confrontation with the undiluted.

Why anyone with any self respect would ever let someone else tell them how to write, how to think, how to keep a journal, how to be—it’s all beyond me. I’m obviously just as guilty of the sin of prescription. But I hope that all I’ve been banging on about is the radical need to go your own way. I’m ever the Emersonian on this. Self-reliance is the soul’s spiritual necessity (which, to be clear, is not exclusive of connection and love). I’m a Marxist of the Groucho variety: whatever it is, I’m against it.

Stoicism. Sure, there’s good to be had there. But there are so many stranger, more productive philosophies! Life needs to be weird to be good.

Lifestyle voyeurism. This is my plea to all writers who read this (and feel free to call me a hypocrite): do not let your work become merely a place for people to fantasize about a different lifestyle. If you do, at least make interesting art of it. But ours is the age of disturbed and voyeuristic living. Anything which feeds into this—which presents a seductive matrix of aspirational habits, accomplishments, or possessions—is deeply wounding to the soul.

Notes: damn you, Substack, for putting these writers back in the Twitterish prison-house of bad epigrams, gamed virality, and self-promotion which kills.

And finally I do not understand my own willingness to let all these fine standards go, the moment a newly promising exception appears on my feed, its promised revelations a mere click away.

5. What’s Next?

I sometimes think that the point of life is witnessing. We’re supposed to be watching this world, and watching each other, watching the birds, the time as it passes by. Pain, or suffering—they’re fog on the windshield, a smudge across a lens, preventing us from seeing the world, from witnessing its operations and its power. I’ve been selfish, and I’ve been a lousy friend to some people. I’ve also suffered a few genuine tortures that might have killed someone else. I myself would probably be dead if it wasn’t for loved ones and the Work. When I get a little space to look at these things more clearly, I begin to see how it was all an obstruction, all noise blocking out the listening I was supposed to be doing. Healing, forgiving, looking for forgiveness—these are their own reward, because they make the lens clear again. For a moment, things are sheer and transparent enough to be clearly seen.

So this is what I’m doing here, in a way. Trying to clear the lens, clean the glass. Wipe away the fog, so I can focus again on what matters—most of which is still to be found in the real world, not on Substack. I do not usually like it here. But I intend to stay a little longer, at least until something better comes along. In the meantime, I want to renew an old commitment, to using this place to do the kinds of things Substack doesn’t quite know how to handle. We’ll see if I can. But at the very least, I’m tired of trying to keep up with the relentless pace of a digital scene I don’t even like very much. I want to see what I can really make.

In a recent piece, I tried to stay away from declaring a New Romantic Era, the way that some (especially Ted Gioia, King of Substack Mountain) have been going on about. Alas! I don’t see much Romanticism yet. Maybe inklings. We’re still a bit too sexless and timid, too stuck in the patterns of the last decade, too far away from even an approximation of a mainstream. But the point of my piece was ultimately that we will not really have a “Second Romantic Era.” We will have something else—something new—which is most appropriate for our moment. Romanticism is something we can look back to as an inspiration, maybe the closest thing to what we ourselves need. But we cannot simply say “Let’s repeat that.” It never works. Consider the Bolsheviks.

So as I put my energies into publishing, performing, and academic pursuits, I’m going to use this Substack as a place for exploration again. I want to investigate and write about this ongoing and peculiarly fragrant “Vibe Shift” thing, yet I just can’t be bothered to care about cultural prophecy anymore. I have to figure out a different way to do it.

In the meantime, three of my own closest friends—some of the very best people I’ve ever known—have started their own little projects here, so I hope you’ll go follow them, and give them a chance. They are:

Ben at Flyover Takes—

Troy at his new Critical Archives—

Hannah at a little world—

I hope you’ll also continue to support The Hinternet, my second home. Justin is a genius, one of the few guiding lights around, and just about the only person here whose “takes” always feel earned, fresh, and profound. There are plenty of other brilliant voices and people in my “network” whom I hope don’t feel left out or disparaged by any of my words, because I do like and appreciate so many writers here. I hope there’ll be a little more interaction in the real world between us, and less behind keyboards. Peace, sweet readers. Be back soon.

Rare to read a post where I see my own feelings articulated so clearly and well.

I found myself agreeing with pretty much everything you said here. "I sometimes think that the point of life is witnessing" - this in particular is a conviction I definitely share, maybe it's partly a temperamental thing too, but it feels so core to my aim as a writer and where most of my joy in living comes from.

Also, totally agreed on the brilliance of Orlando, and on Virginia Woolf in general. She's without a doubt one of my favourite ever writers of English prose. Have you read The Waves? It's so, so beautiful.