Quick apologia: This piece is going to feature some very light partial nudity. (When dealing with masterpieces of art, I’m afraid the naked human form is unavoidable. They tell me the Zoomers and Alphas dislike this kind of thing. I say: get thee to a museum.) There’s also a bit of talk here about the relationship of male artists to women as their subjects. Knowing the internet and contemporary discourse, this is bound to frustrate someone. I can only say that I have much less confidence in pronouncing anything on the special dynamics of, say, women artists taking men as their subjects instead. The whole purpose of this piece is exploratory, thinking through a few things which strike me as true, in a general sense. I wouldn’t be surprised if at the particulars some of them turn out not to work. I welcome any and all comments from readers who feel moved to speak about what similarities and differences they observe in other dynamics. I only ask that it be done in a similar spirit of exploration, not full of certainties, and nothing hurtful.

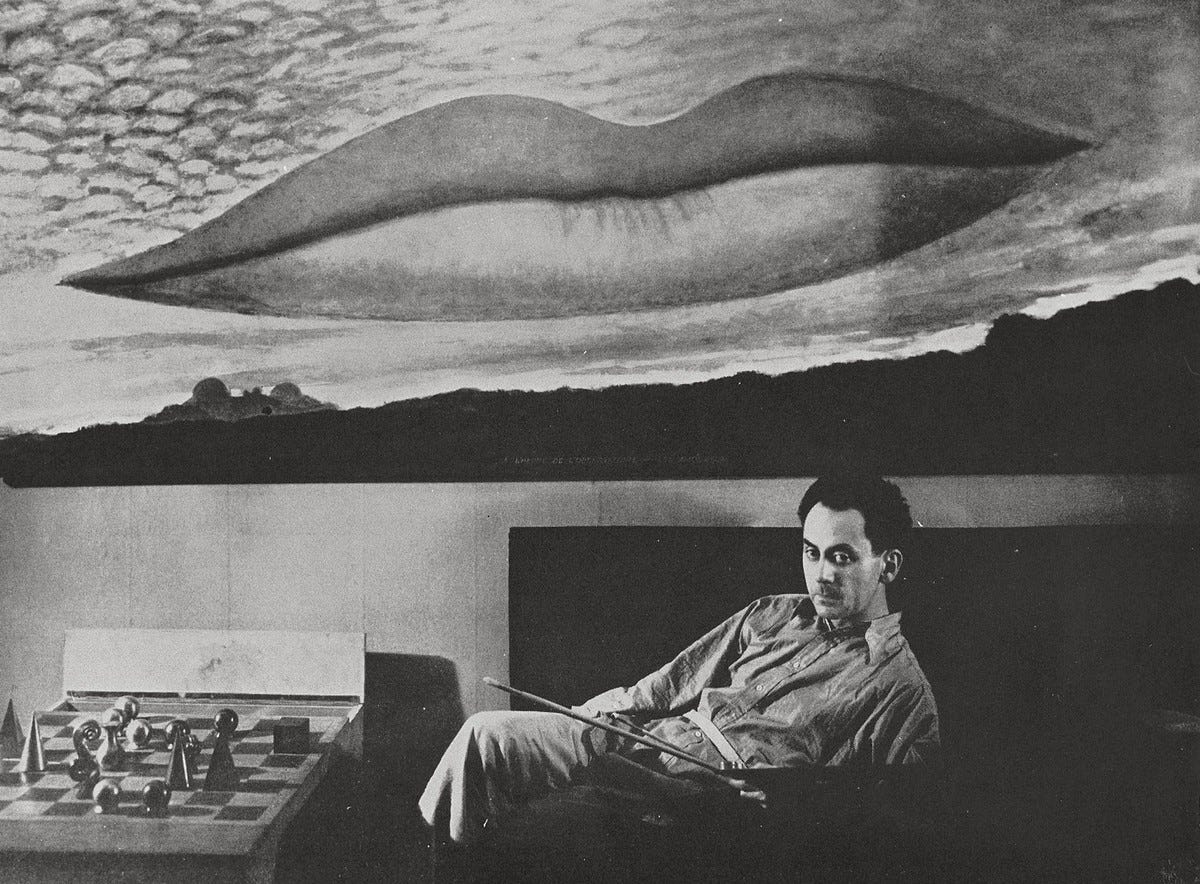

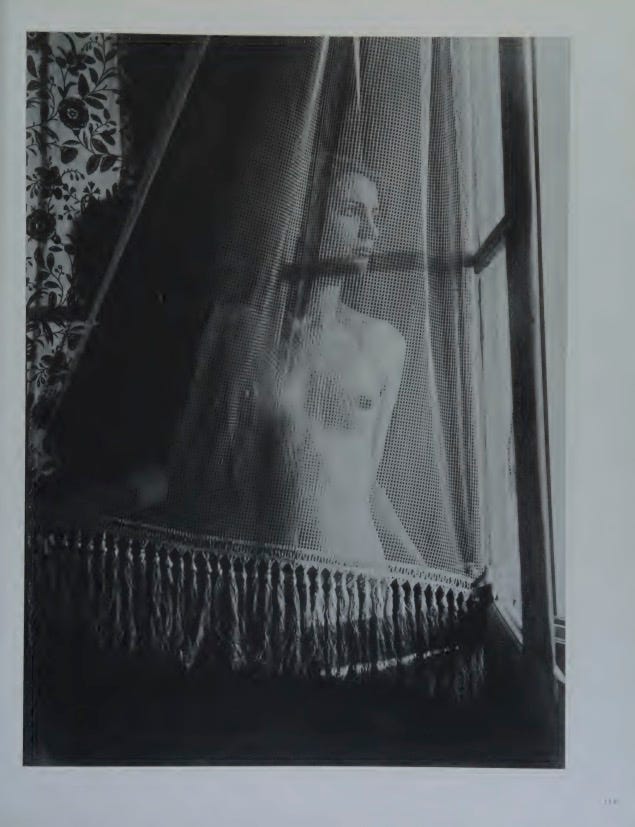

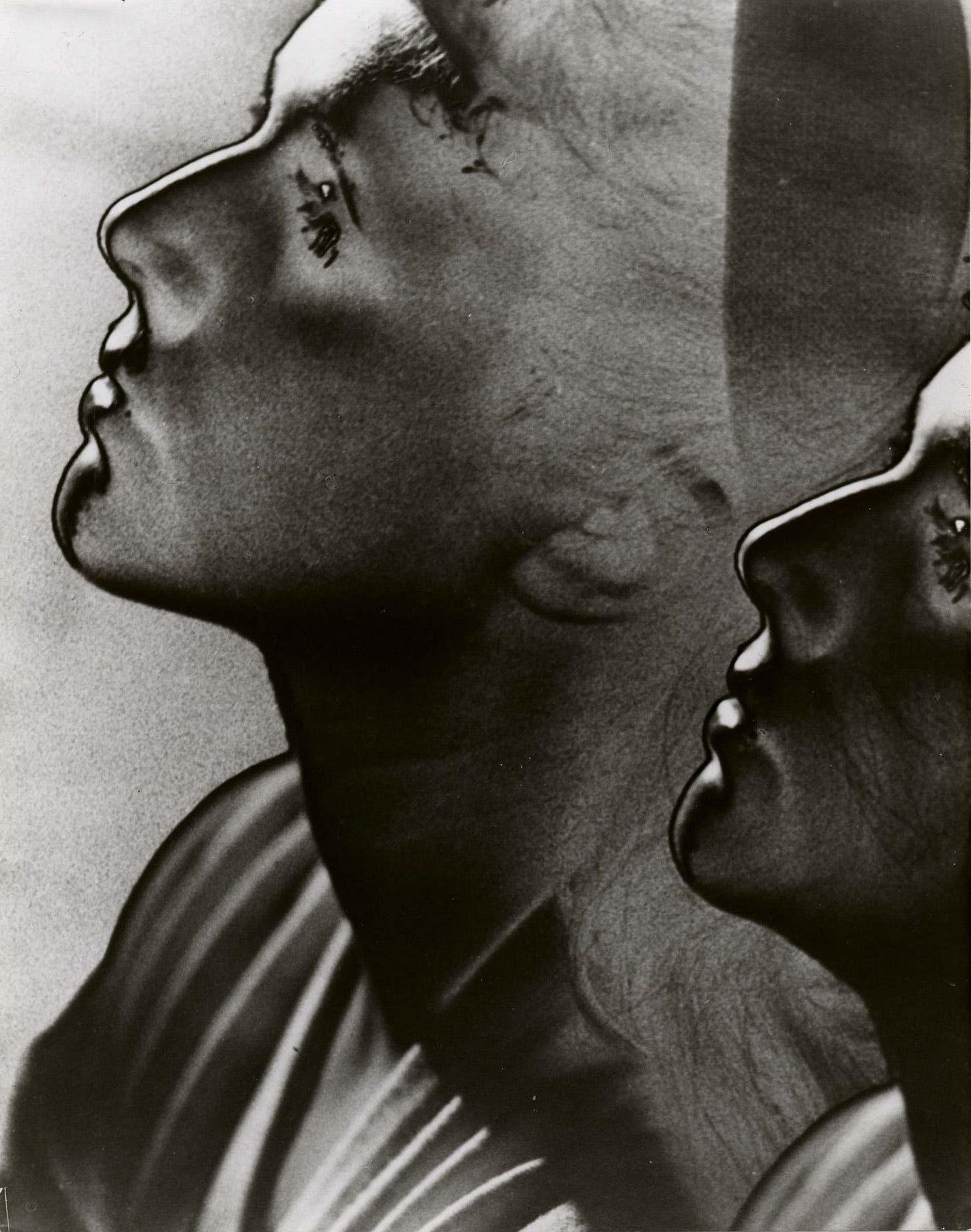

I first fell in love with the photography of Man Ray when I found a collection of his portraits at the public library in St. Louis. I checked it out again and again, and it sat on the small folding card table where I used to eat my dinner; it must’ve sat there for over two years, off and on, reflecting the room. There was one particular photo—part of a triptych, among many legendary portraits Man Ray took of Lee Miller, during their time together in Paris—which hypnotized me endlessly. Partially because it’s beautiful; partially because I am (irrevocably) a man. But of course that’s reductive. There’s something infinite, icy, and constantly beguiling about those famous pictures of Miller. Especially this one:

Like certain other great male-female voyeur-subject relationships (I’m thinking here of Antonioni-Vitti or Godard-Karina or, much earlier, Manet-Morisot), Ray-Miller is a fused thing: the man attempts to look at the woman, at his worst even playing a puerile game, trying to possess her through her image. He plays Pygmalion, though of course what that really means is that the wildness of the myth is soon to have its way with him.1 Since he finds again and again (and again) that she’s simply too interesting, too human for that. And, as in the case of Morisot or Miller, what is also often revealed is that the woman is herself an artist-in-the-making, the pose of the muse only her first attempt at creating the image, done in reverse. Rehearsing for the image by being the image. Still, even in some supposedly “simpler” male-female voyeur-subject relationship, the ultimate truth of the male gaze is that any of its aspirations to containment crumble, at the sight of a proper subject.

To take Antonioni as an example: in L’Avventura or L’Eclisse, the camera doesn’t really do something to Vitti, by attempting to stage or capture or control her image. It explores the world through—and by way of—her peculiar subjecthood. All the same, Vitti certainly does something back to the camera. She’s such a profound actress, such a profound subject, she turns the camera’s eye back on itself, forces the voyeur to confront his or her own voyeurism. The camera pushes in; the director attempts to get closer to figuring out what’s going on here, with this woman. Yet, as with that infinite portrait of Miller, the woman is just too properly mystical (which is to say, too properly human, to an intense spiritual degree). In the end she’s as much a maker as the man who plots from behind the camera. The popular formula—men watch women; women watch men watching them—is just not enough. Because to say a thing is to admit its opposite into the world as well.

For me there was a definable, single moment in which I knew it was fate—or something like it—which had brought me to obsess over these photos (and not just that portrait of Miller, but so many pictures of Man Ray’s). Though I had yet to read the novel, I sat down one night, alone, to watch Philip Kaufman’s 1988 film of The Unbearable Lightness of Being. For a major studio epic, an adaptation of a hugely successful novel, starring Daniel Day-Lewis and Juliette Binoche (arguably the greatest male and female film actors of the last fifty years, respectively), The Unbearable Lightness of Being is somehow these days a mostly forgotten and overlooked film. I find this a minor cultural crime.

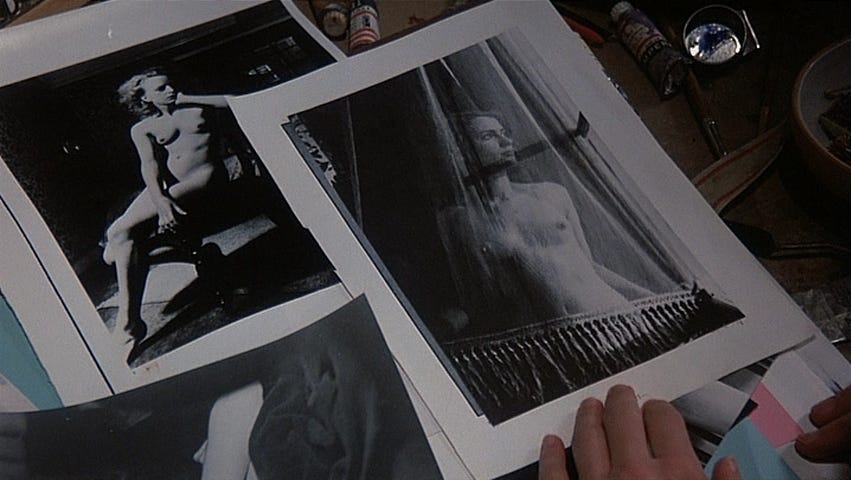

Within the first hour of my first viewing, as far as I can remember, my breath was gone from my lungs, and I knew, as well as anyone can know anything, that I was encountering one of those rare ecstatic romantic masterpieces we live for.2 The contours of the film alone would’ve been enough for me to recognize this, but one scene cemented the fact with such synchronicity I practically vibrated on my sofa. In this scene, Tomáš (Day-Lewis) takes his soon-to-be-wife Tereza (Binoche) to dinner at the apartment of his mistress, Sabina (Lena Olin). Sabina, a painter, takes Tereza, a photographer, aside to show her a print, suspecting that they may share a lot more than just the man between them. And at this moment, in my mind’s eye, somehow I knew—somehow I hoped I knew—what it would be. And of course, there it was:

“They were trying something different,” says Sabina, speaking of the Parisian avant-gardists of the 20s and 30s, like Man Ray and Miller. “Searching for a new beauty.” “Yes. Something higher,” Tereza responds, and the two women understand each other perfectly. If I had to speak spiritually about this moment, I suppose I would say that, yes, there are times when I almost believe that we receive brief dispatches from our futures, or at least from possible futures. Perhaps they return to us like flotsam, unstuck and drifting backwards down the stream: unmoored images floating back from an unseen part of the river up ahead, floating towards us, and floating past us, and disappearing as they follow the river off into the past behind us. Is it possible that the future is not only something we’re making but something which is coming at us? Perhaps it really is as Murray Jay Siskind says it is, in DeLillo’s White Noise:

“Why do we think these things happened before? Simple. They did happen before, in our minds, as visions of the future. Because these are precognitions, we can’t fit the material into our system of consciousness as it is now structured. This is basically supernatural stuff. We’re seeing into the future but haven’t learned how to process the experience. So it stays hidden until the precognition comes true, until we come face to face with the event. Now we are free to remember it, to experience it as familiar material.”

I almost hope it isn’t so simple. Still, I’ve seen places in my dreams which I later found in the world in my waking life. Was it only déjà vu? But it was so much more precise: I didn’t have to wonder why it felt familiar. I knew it was familiar because I recognized it from my dream.

First Lesson: The Camera Steals the Soul

We say a photo captures its subject. We even use this as a gradation, so as to say: “It was a brilliant photo, since it captured its subject better than another photo might, or did, or could do.” We have the gall to mock pre-industrial tribes who blanched at the introduction of the camera, fearing it would steal their souls, but still have the temerity to keep going on saying that the camera captures what it sees. Continually, we use this metaphor of the trap, and it’s no mistake. The camera does this. It steals everything it sees: it steals the soul out of things. This is what we see when we look at a photograph—any photograph. We see the thing in its thingness; we see the thing without a soul. A subject, rendered mere object. Yet, strangely, we discover that things are still quite beautiful, even when they’re not alive. Even merely reproduced, as an etching in light, these artifices—these segmented pieces of the world—are so illuminated, they cannot help but seem like things that still have souls. The glow of the soul goes on even in the death of its capture: the shape of life remains; the titanic object is a titanic subject. Death frames the world yet even its petrifaction can only signify the constant reality of life, whether here or gone. Since reality is the thing which always insists on itself, no matter how much we protest against it.

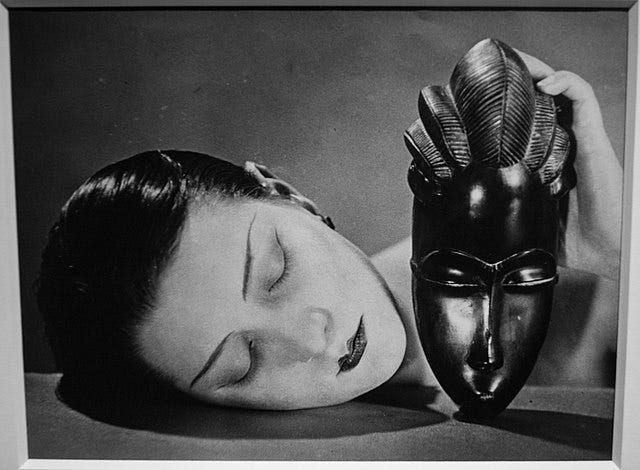

Second Lesson: Men Photograph Women in Order to Be Women

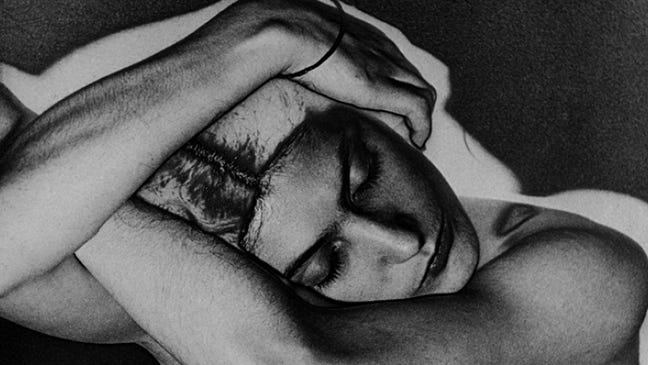

This is not necessarily a transgender reality, though of course it admits of that. Transness often tends towards the esoteric, just as the esoteric often tends towards the trans (see: ancient priests of Cybele, Matthew 19:12, Milton’s angels, and any number of pagan gods). The abolishment of boundary has always been central to humanity’s religious dreams. Knowing nothing about the experience transness myself, I have only a fairly boring and normative heterosexuality to employ here. Still, even that’s enough for me to confidently state that men and women are always trying to be each other, and also to be like each other. Real heterosexual pleasure—real frisson—probably emerges from some space in which two people can play with that dynamic productively (surely homosexual pleasure does, too, but again, this is something I know nothing about, save by report). Which is not to get into any academic talk about gender roles, or patriarchal pains, or any number of reasonable grievances. But neither is it to be naive. Just as Antonioni photographed Vitti in an attempt to understand modern alienation through the eyes of a beautiful modern woman, so Man Ray’s photographs of Miller (or of Kiki de Montparnasse, seen above, or even of the famous “female impersonator” Barbette, seen below) are meditations on the seemingly infinite distance between men and women, and the ironies which plague it. The central irony being that what in one moment seems like a gulf is, in the next, only a sliver. (Though of course what seems like a sliver could just as easily reveal itself to be a gulf).

Across that sliver of a gulf,3 the male artist may certainly regard the female subject as some dull pedestalized goddess, or else something even more banal and pejorative: a “low” woman; a hag. These turn interesting subjects into mere misogynized objects. Truly dead things. But in better art there’s surely an element of trying to approach what can’t be approached through everyday means: trying to approach the woman in the man, and the man in the woman, though not necessarily collapsing into androgyny (since one thing androgyny might be is something like an aesthetic which has been completed, and no longer stimulates: it lacks the conducive dance of opposites). In genuine works of art like so, the male artist is indeed contemplating something he cannot quite access in himself, since to become that thing would obviate his existence as a man. Perhaps this is something which transness can solve: though it seems only to solve it in some of us, and not others.4 With male artists it may appear as a productive tension, since it rests on a gamble: will the woman as subject remain a subject? Or will the man betray the subject and reduce this person to a thing? When and where does that line get crossed? Precisely where does this become an immoral act? Here I leave all further paradoxes to the philosophers and say only that great art is often a matter of making two apparently opposite things seem equally true, and (even worse) seemingly dependent upon each other.

Third Lesson: Realism is Surreal

Fiction is reality pretending to be real, and photography is only another fiction. Though, of all fictions (aside from cinema, the vivid Athena which springs from photography’s skull), it is the most real. Therefore it is also the greatest lie. This is surely one insight behind Surrealism, Dadaism, Futurism, and Modernism in general. A photograph is such a powerful lie it changes our relation to our own sight, to ourselves. In a world like ours—of constant, exhaustive documentation—perhaps only the willingness to be so exquisitely artificial, to lie beautifully, can redeem us in the act of making such images.

Is it that tears are like glass, or that glass is like tears? How many high-flown, affected poets have compared weeping tears to the pooling of the ocean? And yet this height of artifice, of comparative fiction, turns out to be true as it reaches the scientific age. Evolutionary science teaches us that life grew in the oceans: our eyes first developed there, and they were never meant to see, except through it. So now we have to carry the ocean with us, wherever we go, keeping our eyes afloat in that same saltwater. And so every ocean is an ocean of tears, and every tear is a model of the ocean. So say that since glass begins as sand, isn’t Man Ray’s photograph, on some occult level, only the sand pretending to be the ocean? Modernism is just the collected techniques of artists bent on revelling in this upset of meaning, which of course returns us to an older meaning: the new, full efflorescence of metaphor, expanding technologically towards the cosmic.

Artifice, metaphor, figuration—we treat these things as “unnatural.” We treat them as constructed, all-too-human. Far from a wilder, somehow truer, nature. Yet as Wilde says in that gorgeous work of heresy, The Decay of Lying:

At present, people see fogs, not because there are fogs, but because poets and painters have taught them the mysterious loveliness of such effects. There may have been fogs for centuries in London. I dare say there were. But no one saw them, and so we do not know anything about them. They did not exist till art had invented them.

Did anyone ever really cry tears like the glass ones in Larmes? Anyone who was ever heartbroken certainly felt like they did. In the context of a photograph, what exactly is the difference?

Fourth Lesson: The Camera is a Room

In Latin camera means a room, or a vaulted chamber—a meaning which it gives to all its daughter languages. It enters its common meaning in English with the camera obscura, the predecessor to the modern camera. Yet even our modern camera is still a room: a closed-off darkness, into which only a little light may be allowed, enough to burn its way into nitrate, or celluloid. Of course, the camera is also itself an eye: it has a lens, it takes all light in upside-down, in a picture which must then be turned around again if it’s to be projected into anything meaningful to us. The ancient Greeks thought eyesight worked like a spotlight, that our eyes shone out their eyebeams and illuminated the darkness. But what they described was a projector, not the camera itself. Not the eye. Since the eye is also a room—a dark room, into which some light leaks in, burning a picture in the chemical compounds of the brain. It is the brain which takes this image and turns it around, projecting it back into our consciousness. The brain is the first movie theater. (Though we must also speak of the darkroom of the mind.) Just as in the movie theater, from one dark room to another, we reverse the process of our own seeing, and reverse the process of the camera, we project the image back onto those dark cave walls. Then we sit and learn just what it is that eyes do, even when they’re closed with dreaming.

Lenses, rooms, cameras, eyes—a Man Ray photograph collapses the difference, departs so much from the “imitation” of mundane reality that it builds its own dimension, a room where surface, light, and figure serve their own purposes. Here they’re freed, and they begin to behave roguishly. In his rayographs and solarizations—all throughout his most extraordinary experiments—his work is more prophecy than mere representation. There is no “nature.” No “outside.” There’s a vision in a room, on a blank plane receding into infinity. Almost nothing is more truly avant-garde than this: it’s pure spirit, pure form. Does this spirit conflict with the photographic universe of death, that risk each photo takes of making only hardness, coldness, or stultification? Only in our mundane material world does death “conflict” with spirit, or nature, or life. In the ideal world—the world of art and artifice—we see the visions behind these things. Forms. Daemons. Possibilities. Dreams. Rooms and rooms of lenses and eyes seeing more eyes. Mirrors on mirrors, projecting into the dark.

Final Lesson: Beauty, Beauty, Beauty

“Exuberance is beauty,” says William Blake—and the entire universe attests to the fact. Renaissance humanists wrote that their poetry should be filled with enargeia (ἐνάργεια), an incredible sensorial vividness; though even above that (and above most other literary virtues) they praised copia—abundance. A great artist overflows; he or she runs over and runs over and is never truly exhausted. Their works are endless, too. They alone may say with Shakespeare’s Juliet: “My bounty is as boundless as the sea,/My love as deep; the more I give to thee,/The more I have, for both are infinite.” For them, their figures vibrate: they spring from inner lights so unquenchable, even death seems secondary. Against a universe of shit and death and darkness, they cut the tiniest sliver in the universe, and make from it a gulf; they form the tiniest aperture, letting in a little light; they build an artifice with which to frame the world, and give the world its own visions back. They build for the world its proper room.

I am just a man: another man in another room. Trapped in his visions of women; moored in the desire for some more transcendent sight; desperately confusing the two. I rise up and up and into that transcendent black-white plane of a photograph by Man Ray. I see the profanity, and the strangeness, the exuberance and beauty there. “Searching for a new beauty.” “Something higher.” Yes but look at these pictures—these holy, holy pictures. Some life remains in them; some soul, or the glow of a soul. But we cannot live in them. The vision in the end is just a vision, and no one can ascend forever.

The world remains the world; the glimpse behind things—which the photograph offers—is, after all, only one moment, vivisected from the flow of time. Another future, or possibility, floating back to me, from a bank on the river somewhere far up ahead. Gravity brings me down; the coolness of the earth is not like the coolness of death, or space, or a photograph by Man Ray. Exuberance is beauty, yes. But then so is rest. So is sleep. I close my eyes, and let the river drift where it will. In my dreams, more visions come floating by, catching in the eddies, in whirlpools and flashes on the chemical substrate of my brain. I close my eyes and they pass; I close my eyes and each floats away again. This is how it should be. The vision goes. Beauty fades. I sleep when it’s dark, and then the day brings a little light. When it does, the vision starts up again, and I see—I see that the room remains, and must still be made more beautiful.

Though of course Galatea begins as a statue, which the artist wishes to bring to life—so it may be more apt to say the photographer is Pygmalion in reverse.

If you haven’t seen the film, I cannot recommend it highly enough. It’s the last masterpiece of its kind—the last attempt at a New Hollywood register, and somehow also the last attempt at an Old Hollywood Romantic Epic. Equal parts high and popular art, in ways that I think should frankly embarrass contemporary filmmakers.

Or that gulf-sized sliver.

Indeed, part of the “difficulty” of the existence of transness is that rather than reducing us to societal creations, it seems to prove instead a human nature which survives even the harshest social pressure.

Your footnote 4 is quite a beautiful statement, and an essay in its own right (although nothing else needs to be added to it.)

I also appreciated what you said about gender tensions being more fascinating (real?true? important?) when they remain unresolved. I have found that to be accurate to my own experience as well.

Your part about the muse-as-artist reminds me of Jacques Rivette's beautiful movie La Belle Noiseuse, where the artist (an old man) keeps putting his young, beautiful model in different torturous poses, unable to get to the heart of her beauty and essence until she herself gets fed up and starts to come up with her own poses that feel true to herself.

I love the idea of the eye as a darkroom that processes the images we get from real life! I first saw Man Ray's photographs when I took a darkroom photography class in middle school, and I still remember how much I loved being in that darkroom, figuring out how long exactly to expose a picture, the smell and swish of the chemicals, hanging the wet photograph up to dry.