In the final installment of these essays, I’m picking up from where I left off in the examination of the obstacles facing artists today. In Part 1 (which you can read here), it was the regime of moral didacticism, which plenty of writers here on Substack have railed about. In Part II (here), it was a centralized anxiety about the past, and the unwillingness to let it live in the work we make anymore. In Part III (here), it was the long replacement of wisdom with science, and the panic over technology. Now, in Part IV, I’ll see if I can’t bring it home to where we actually live, to the need for shedding some of this baggage in order to actually get going on the New Era we’re all beginning to talk about.

But first: a huge thank-you to everyone who has read and subscribed thus far, and even commented on these pieces. What happens next at Vita Contemplativa will hopefully be varied enough that everyone can find something of interest, whether that be weird poems, or speculative fiction, or just literary essays, or even attempts at outlining new canons. Hopefully I’m already going out on a few limbs and risking looking like I don’t know what I’m talking about—that’s the surest way of being a fool, and only a fool is ever going to get anything right in this place. So here goes.

The ideology of personal growth, superficially optimistic, radiates a profound despair and resignation. It is the faith of those without faith.

Christopher Lasch, The Culture of Narcissism

So: the twenty-first century artist is in a truly unenviable position, faced with an unholy alliance of technology, despair, and solipsism. Our impasse—the sheer amount of tradition and knowledge in the arts which has been lost or discarded or ignored in practice—seems impossible to confront.

But it’s still useless to make elegies. Given the course of the twentieth century, this movement was inevitable. To any artist attempting to resuscitate or reconnect with the ancient Voice, it does little good to lament long periods of drought. Instead, consider that what we’ve seen these past few decades has been, in its way, the proverbial wandering in the desert. With time, the constricted contemporary voice (which is often reduced by its critics to the techniques of deconstruction and conceptualism but is really composed of much more prosaic stuff) looks a lot like the desperate thrashings of a traumatized century which, having witnessed the darker possibilities of belief, would simply have no more of it.

Because belief is deeply inconvenient. For critics and artists alike, it’s the wrench in any system, that which ideology itself must work double to assimilate, which even the dullest cultural prescriptivist can never really account for. And given that belief in the possibility of new meanings is so necessary for creation, yet so difficult to muster, there has always been something of the Holy Fool in the artist. A combination of earthy reality and heavenly ambition—a discordia concors—which has to happen if the imagination is to unstick itself from its confining social circumstances. But we still have to face the fact that there is something—almost the sum of that unholy alliance which created our impasse—which needs to be understood for artists to break their way out and start their work again. This is the most difficult and slippery modern reality: our narcissism.

Slippery, because it’s so difficult to separate our narcissism from our calls to progress. This isn’t the fault of anyone, only the way things have played out over time. So, any artist who wants real freedom to create would probably be wise to work hard at having fewer political convictions. Of course many will object that there have always been political realities involved in making new art. And to this end, the reigning contemporary ideology, having long ago rejected the idea of aesthetic standards, has had to develop a curious rubric for the age of relativism: as far as there seems to be any “philosophy” behind the output of the current creative industries, it’s mostly that hobgoblin “identity” again, with its ideal that art ought to be the vehicle for the subjective experience of the artist. And since there can no longer be any real argument about whether a work of art is better or worse than another, the stated goal of so many arts institutions is now merely the rolling, indefinite extension of this solipsistic privilege to people who until recently didn’t have the luxury to express themselves in such a way.

The irony of this situation is, as I mentioned previously, that it has resulted in such a stunning cultural uniformity of voice and manner. Rather than illuminating the human experience from a genuine variety of perspectives, it has turned everything into that same declamatory, hectoring voice, indistinguishable from the language now used all across social media and in advertising. Yet this is where things can get very quickly confused. Because the establishment of this manner happened in tandem with an increased academic preoccupation with Theory, and with public interest in social justice, it has gained enormous rhetorical support from those professionalized creatives who are concerned with giving their gatekeeping power the appearance of moral virtue. That vocabularies of political representation (along with pop-therapeutic ideas of self-esteem and empowerment) are routinely brought in to justify so much of their production is itself the best proof that it has no intrinsic merit or aesthetic value on its own. And that, deep down, its most ardent proponents know it. Hence the powerful desire to stamp out any criticism which is not overt advertisement, or which insists on anything like an aesthetic standard. That such a standard necessarily has something to do with the oppressive history of Western culture, the same professionals and academics never tire of telling us. Yet they are rarely challenged to offer up anything more coherent, let alone any longer-lasting traditions, or canons. The discomfort which is clearly caused by even slight negative criticism shouldn’t surprise anyone capable of some insight. Because it is in itself a kind of narcissism.

The narcissistic pose is hardly unique to the creative industries. Christopher Lasch laid this out prophetically in his 1979 The Culture of Narcissism, still an inevitable touchstone whenever the term gets used anew. And it remains a practical bible for understanding the dominant contemporary mode. For any artist, wrestling with one’s own faith entails wrestling with one’s own narcissism, which is its spiritual opposite. As Lasch pointed out, narcissism is not merely a clinical term for behavior but something we have tended towards in all aspects of our society, something our society is shaped to encourage and reward. Each of us shares in it to the degree that we easily believe ourselves exempt from the thoughts and conclusions—now even the physical presence—of Others, and find ourselves using technologies which amplify the grating contradiction, just as they allow us to assuage the anxiety which they simultaneously produce. But when this pose is found in the arts—where freedom should be paramount—it’s doubly hypocritical. And it’s not merely the gluttonous, self-obsessed narcissism of the popular imagination. It is much more mundane, and more tragic.

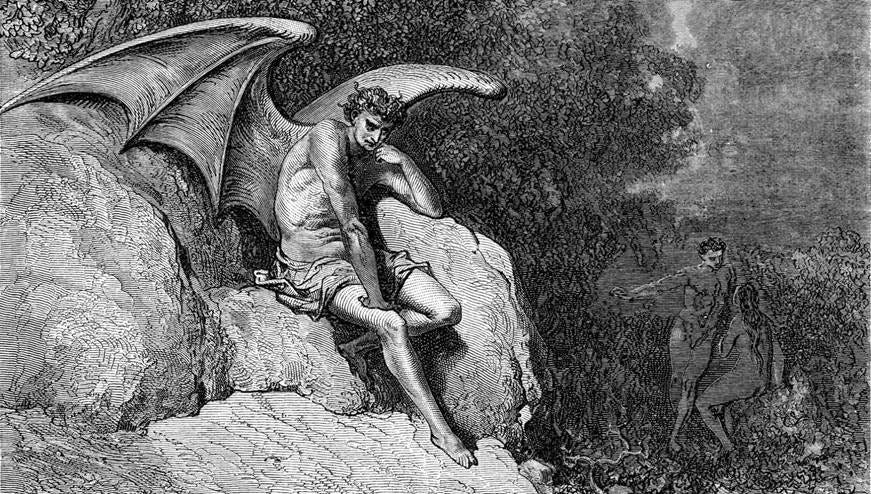

The narcissistic pose is the pose of the overwhelmed, of people who are anxiously ashamed of their inherent lack. For artists especially, it is a reactionary impulse against that “mischievous” Bloomian-Emersonian sense of coming too late to a past and a culture already very old and established, which may not even need our contributions at all. It descends on me when existence feels so fragile and uncertain that I have to organize and manipulate the world and the people around me, in order to ward off the possibility of negative emotion, or judgment from inside my own self. Because these things might wake up the even crueler, punishing spirit which emanates from deep within my lack. What Blake called the Covering Cherub—the sword-wielding angel assigned by God to guard the Gates of Eden after the Fall, which Bloom later identified with the burden of precursors—transforms into the cruel tyrant god (which is also Satan, the prosecutor, the Adversary), sitting in the superegoic seat of the mind, torturing our little egos for all our failures. And it tries very hard to keep us from going any deeper, since to do so would be to plunge into the deepest part, to the esoteric Self, free from the transitory self still writhing at the surface.

Hasn’t this pose become something of a universal contemporary character? All our discomfort with older systems of morality, with Nature or with natural urges, with the idea of inherent qualities, talents or values, with belief in self-transcendence, even belief in God—this discomfort is caused by the persistent twinge of recognition, that we are not nearly as unique in our personal experiences or expressions as we had hoped. That a work of art is ultimately profound because it is the product of a difficult simplicity, a simple difficulty: the dedicated work of people rash enough to believe in the new, ridiculous enough to try, and unselfconsciously willing to fail. There is, and always will be, a simple faith in the work of any artist—even against apparently convincing evidence to the contrary—that something universal and lasting is possible. To survive, an artist must recognize that she is, very seriously, engaged in a struggle with a mass societal urge, present in all times and places, which is continually trying to eradicate its own inherited wisdom. The ancient need to kill the parent, in order to believe as though one has birthed oneself. And the contemporary neutering, even outright abolition, of such an ancient category as Wisdom (and its diversion into Self-Help or Expertise) is only the subtlest, most skillful attempt yet. So artists must get wiser and subtler, too.

If there is properly a place for the artist at the Aesthetic Turn, in a century which looks to be another confused and catastrophic one, it is surely in the search for those forms and values which the contemporary world has cast aside in its rush towards numbness and distraction. The faith which is required to make something new can only be found there. It may be that this necessity can only be felt as a necessity when it is recognized as a genuine final chance—until that day, it may seem fanciful or naive, even a bit ridiculous. But then the day comes, and it’s all there is.

No technology will replace our need, no identitarian indulgence will make us feel whole, and no political program will ever liberate an artist into his or her own imagination. We have to get there in quiet, diligent practice; in beginning the work of the new, which is of course only the very old. In a way, it’s as simple as growing up, and getting over ourselves. Growing past the infantile anxiety, towards the resigned faith which Blake so beautifully called “organized innocence.” It’s the work of the Voice—that same nature which reads, which writes—the nature within us and outside us—a selfhood behind the self—a personhood beyond personality. The Mystery, by whatever name we call it. The place of the artist now is not a nowhere, not a nullibism, though it’s continually mistaken for one. The place of the artist lies in returning to the great flow, which runs backwards and forwards, sometimes visible, sometimes not, yet in the end is the only place where the transitory fixations of the age no longer corrupt and distract. It’s a sacred place, requiring some sincere cultivation of the sense of the sacred, no matter how embarrassing that sounds.

The Mishnah says, “You are not obligated to complete the work, but neither are you free to desist from it.” When we believe we have lost faith, then in some dark, obscure way, it was precisely because we wanted it to be that way. And this is the hardest, easiest thing in the world to realize. But looking for that faith again—that means going off into the weeds. Getting properly bored, and properly lost. And though you may often hear otherwise, that is the very best place to be.

Thanks again for reading. More things to come soon.

I thoroughly enjoyed this series Sam, both the content - which as you might predict, resonates deeply - but also your very fine expression.

I'm so grateful to work with an artist who (in my opinion) has been following these profound pointers for his entire career and has deftly avoided the traps of which you speak. But the market fears to reward those who shirk the dogmas of the day.

Thank you for being willing to take up so much space for this series. A year on these essays are still as water to the desert.