“How well he’s read, to reason against reading.”

William Shakespeare, Love’s Labours Lost

Proem: History is a Palimpsest

There’s something floating through the microwaves, whispering in the message boards, broadcasting through the terminals of Substack Central, land of frugal tech men and agonized scribblers, digital clerks at their desks in an age of collapse, days of the ironist, the betrayal of the clerks…

What this something is, though—who could say? Speak of vibes, and we only the invoke a kestrel, an opaque and gyring muse of the airwaves. Speak of religion, and from deep subterranean lakes of oily history, we summon the titans of another apocalyptic century. Speak of Romance, and the questing idol sets off again into a map of dragons, another little bark-like soul adrift in the ether. What’s coming is too strange to see: it tapers off at the horizon, and who’ll be foolish enough to name it?

Because what’s coming must be new—must be strange and fitful, awkward and passionate. A lover rediscovering the world, confused by its tactless kisses, yet charmed, endlessly, by its dents and imperfections, its sadness and its religion, the dimples where its ancient smile shows.

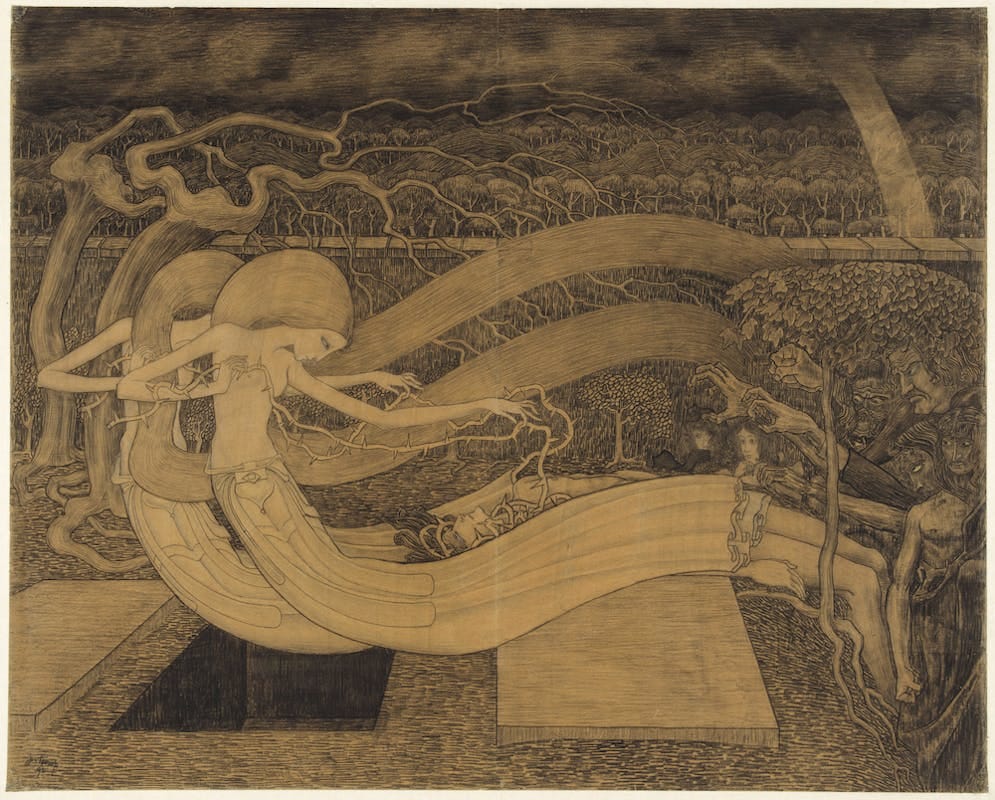

History is a palimpsest, and the world piles up its dreams on the scaffold, only to turn sometimes and erase or fill it back in where it wants. And yet as Emerson teaches us, “There is no history, only biography.” The surfeit of past lives might drown us—so we should understand the palimpsest, observe as one text fills in the margins of another, and each new era builds its icons with the husks of older ones. Remember that each new movement (to call it that) emerges, not out of any grand new theory, but because it has aligned itself with the pasts in which it recognized itself. The Romantics didn’t invent Romanticism: they saw themselves in Gothic architecture, in the medieval romaunce, in Dante, Shakespeare, Vico, Rousseau. They found their accounts of the passions in the Classical World, their myths in an ancient Paganism, allied to a tremulous Christianity—and in all these strains they recognized something they could call Romantic. There was no single resurrected Past but a collision of Pasts—specifically those they deemed most relevant to the present, or most conducive to the future.

So, though I’m open to other names for it, I cannot think of anything else to call it—I want to believe in New Romanticisms. I admit that all artistic and social movements are foolish. Yet it’s the willingness to be rather beautifully foolish which marks the most interesting ones. Every new shift, every new movement, must take into account the shifts and movements proceeding it, and this is why it only grows harder and harder to start—nothing has ever been so heavy, though the digital world seems so confusingly light…

Interlude: The Betrayal of the Clerks

I recently had the interesting experience of giving a talk on paranoia, the text of which you can read here. I found myself stumbling into a kind of anti-Gnosticism, which I didn’t exactly expect. For some at the talk, this seemed welcome, perhaps clarifying. For the more conspiratorial among the audience, I could see a slight annoyance. It was painful to feel dismissed—it always is. But I still think that in private life, as in the act of creating, paranoia’s of no use whatsoever, except as a means to better understanding human character.

At the same time, I was working on an essay memorializing the controversies of my beloved Harold Bloom (which you’ll hopefully be able to read in The Point sometime later this year). And though I'm somewhat sympathetic to people who find the old melancholy dinosaur tiresome, strict, or backwards (and have recently felt some of the same), going back over select interviews and writings, I find the same glow I once felt emanating from even his haughtiest proclamations. I have to simply admit that I love the man, who was the most important teacher I ever had, despite the fact that I never got to meet him. When he opines on the state of academia, I take it with a heavy grain of salt (though I think he was broadly right: academic literary study overflows with the hatred of literature)—but when he recites a poem, or sermonizes on the power of reading for steeling the soul against a desert of meaning, I find the same old warmth and comfort I’ve always found in listening to that Voice. I know, and feel immense strength in knowing, that this is my teacher’s Voice. And though I can depart and challenge the Rabbi in any way I wish to, I’ll always be called back. Because this is a Voice which tasked new artists with the work—the real work, not this scribbling and hustling and digital rambling, whatever you want to call it—and I always feel as if I’m lost, until I remember to answer that call again. I’m no critic, really, but a poet at my root. The Poet is the figure for all writers, the type at the bottom of all writerly types. It’s also, as far as I’m concerned, the only thing worth trying to be in this world.

Literature is not merely a form of life but is, as Bloom once gnomically said, the only real form of life. I take this to mean “Form” in its aesthetic sense—the filled-in qualities or shapes of life, which have no appropriate form until they’re placed in language, character, and narrative. If there’s properly no history, only biography, then there’s no distinction to be made between a biography of the self and literary character. So I’ve been reflecting lately on the idea that all things, including selves, are ultimately literature—or perhaps that literature itself is the figure which life takes, in order to best understand itself. Philosophy, religion, and science are admirable tools and fine life pursuits. But I think it’s only to the degree that these disciplines become arts that they can help us to understand ourselves or the world. This feels especially relevant to my current tour through the academy—professors and scholars go to great lengths to assert that their narratives and questions are somehow “more true” than the works they study. Yet it’s all literary. The scholar is a literary character; the academic is a living trope. High scholarship is only another heightened fiction—sometimes gloriously so. Its kind of fiction is merely playing a game which says “Pretend for a moment that all we’re doing is describing someone else’s game.”

In short, if you put me in front of a class of GPT-reliant freshmen, and tasked me with convincing them to do the actual work, I would try to persuade them that literature is the only real way to understand the world, because all things are imaginatively reducible to literature. You have to read something. Whether you’re an Australian aborigine reading a landscape of stars and rocks, or a digital explorer combing through networks for guesses at the next great shift—you yourself will have to read something, and read it deeply, or you’ll never understand your place in the world. And that is something no philosophy, religion, or science will ever be able to authentically tell you.

So if there is something to these New Romanticisms—something substantial—it’s going to be genuinely literary. It will abound with cosmic irony, rushing outwards in an unselfconscious need for the an art. For the Work. And with all apologies to digital enthusiasts, it’s not going to tolerate the gripes of lazy or distracted people, not going to stand the snake oil salesmen of a new tech wonderland, or to care one iota for the microcultures of the internet. It’s going to carve out a place—any place—where the freedom to think might be nurtured in the real world, where new teachers can find new pupils, to profess and to hand down the responsibility. As the Pirkei Avot says: “You are not obligated to complete the work, but neither are you free to desist from it.” All digital enthusiasts risk being on the side which ultimately opposes Memory (whether they accept that or not), and are therefore discretely anti-human, and anti-literature. I know that if I have to choose between literature and politics, or between literature and tech, or between literature and science, or anything, then I will always choose literature. Because for me that amounts to choosing the World, and choosing the Human. The World and the Human—our finest literary creations. Each needs the other to exist, just as we need them.

Interlude to an Interlude: Mal du siècle

Several weeks ago, I had the equally interesting experience of attending the first of what I hope to be many events, held by my new friend August Lamm. I don’t know August that well yet, but I can certainly say she holds a room. The event was the first foray into what she’s termed Archaic Networks, a constellation of ideas which I absolutely love. But what struck me most was the sheer appetite in the place—a pub basement with maybe thirty or forty people of varying ages, coming and going—for some honest-to-god real-life communion with similarly-minded strangers. And a similar appetite for digital de-programming and anti-techifying, for which August is quickly becoming one of our most persuasive evangelists.

As another friend and I agreed, there was something genuine stirring happening there. I watched young people throwing ideas around for low-tech meet-ups, Situationist-style wanderings, magazines, book clubs, etc. A passionate young man in a beautiful brogue orated about the necessity for renewed anti-fascist political involvement, at which a younger computer programmer and an older gentleman of some erstwhile tech-utopian persuasion chimed in to advocate for some similar radicalism. Briefly, they held the room, and the rest of the group seemed to itch and squirm in unison. I recognized the moment. I’ve seen it in DSA meetings, DIY punk spaces, college classrooms, progressive art galleries—I’ve seen the way the most puritanically passionate can hold entire assemblies hostage, through a merciless appeal to personal guilt and crowd timidity.

A few years ago these voices might have derailed the whole evening. But on this night, all it took was a quick reassertion of the actual goal of the event to get it back on track, and in a moment, the directionless urgency of political rhetoric had taken a backseat to the important stuff again: to art, to people, to being present at that moment. It was one of the healthiest things I’ve seen in a long time; it was exciting, kind of sexy (is there anything more sexless than twenty-first politics?). We’ve grown up a bit, I thought, from our adolescence in the trenches of radical politic yearning. Maybe the Right doesn’t have a monopoly on the post-Woke, I thought. And besides being frankly cruel and pathetic, I’m inclined to believe that the whole of the ascendent Right-wing attempt to “reconquer culture” is as empty and full of air as the previous “Leftist” or Progressive chokehold was. Which is good for those of us who care about culture beyond sociopolitical fixations.

I reflected on a conversation with one of my best friends, Troy Sherman, the curator and art historian behind the Midwest Art Quarterly which—like the Caesura folks, or Sean Tatol over at the Manhattan Art Review (both of whom Troy’s sometimes in cahoots with)—has served as an earnest return to art criticism with actual aesthetic concerns, not just the empty signifier which “identity” as become. Though, as we talked about, we’ve only just begun to get comfortable again with calling art “good” or “bad.” Which is very necessary for a serious culture—the opposite of the rabid junk fandoms we’ve been subjected to over the last few decades. But it can’t stop (as the Dimes Square phenomenon seemed to stop) at the freedom to say “this sucks” and to be vulgarly opposite, perhaps followed by whatever once-cancellable slurs you care to say. There can’t be good criticism without good art: the artists have to find their critics, the critics their artists. Of all the things Dean Kissick has said about his Harper’s article, I think the most meaningful was to ask curators to become champions of artists again—to ask that galleries stop caring so much about audiences.

Polemical Extroit: The Ironist as Saint

So what will it be? Will we be pale fatalists and young martyrs? Will we summon gothic rot and heavy weather? Other minds and pens will have to say. I write this to clear a space for myself, and for you, too, if you wish, because I feel the constant creep of decadence—our addiction to decadence, the Internet as decadent trap, keeping nature out. My generation’s cultural output disturbs me, endlessly. We’ve produced some wonderful music, some fine films, Girls. But so little, ultimately. People insist otherwise but they’re deluded. Our prose is overwhelmingly insipid, unstylish, and narcissistic; our poetry is totally bereft of history, cadence, or rhetorical power. That will change, but whether it changes quickly or slowly is all down to people. And the only way for that to change is for us to read more, and spend less time with most technology.

I’m disturbed, too, but what I see on this website. I’m sticking around for now because I see things—the new Metropolitan Review, the happy playground (and my second home) which is The Hinternet, along with certain essayists who’re entirely earnest and interesting—which hearten me. There’s real passion. But I also see the creep of supposedly “responsible” AI apologists (which is a disaster for the human mind, you philistines cannot convince me otherwise), people so quick to welcome the coming non-literate paradigm, and many more tripping over themselves to list the reasons we can never surmount our own distraction and apathy (which only disguises the desire to give up on the same). There is no room left for anything but celebration of the Human and the World.

If you aren’t reading deeply, creating new arts, or studying how to survive a catastrophe of language, you’re wasting your life. The days of rationality are gone; the days of technological hope are departed. The future of the Word belongs to the Fools again, because we are the only ones sane enough to forego sanity. The “responsible” among us, the “conscientious” have abandoned the Word. So we—the Fools who refuse to let these beautiful old things die so quickly—must rush in, where all our erstwhile political angels have failed to tread. Most people who write are cowards who have nothing to say about beauty, or art. That’s the internet, the industries. But most people in the real world want connection and love. They are floundering, drowning in the hell of society. New Romanticisms will speak to them. Its artists will grow unafraid to preach, or to exhort. They will commit to a world and a new style of endless play and unfettered imagination—commit to a cosmic irony which can reach even the most distracted and isolated soul. They will be Fools for the World, and their New Romanticisms will be the only cause worth joining.

I am so glad I read this today. My cold cold heart feels a little defrosted. Thank you ✨🌼✨

really really liked this - I’ve been thinking myself a lot lately about what a new romanticism means, what it would look like and how it would manifest now (the title of my own publication is a reference to that, haha) I’ve still got a lot to read into, and at some point actually start getting some thoughts out, but you’ve given me much to consider!